WVU Football Innovators – Dr. Clarence Spears

August 02, 2020 09:00 AM | Football, Blog

MORGANTOWN, W.Va. - Throughout its history, America has had a great tradition of innovators from Benjamin Franklin to Alexander Graham Bell to Thomas Edison to the Wright Brothers to Nikola Tesla to Steve Jobs and Bill Gates.

Innovation has also been vital to the development of football.

The modern game of professional football can be traced back to perhaps the greatest sports innovator of all-time, Paul Brown.

He was the first coach to use game film in order to scout opponents, hire a full-time staff of assistants, test players on their knowledge of the playbook, establish a practice squad and adopt the facemask to protect the participants.

Brown was also among the first to communicate with another coach sitting above the field in the press box, and he advocated putting a radio transmitter in the helmet of his quarterback to share plays, which is now common today.

College football, too, has had its share of great innovators from Walter Camp, Pop Warner and Knute Rockne in its early days, to Don Faurot and Clark Shaughnessy before World War II, to Emory Bellard, Bill Yeoman and LaVell Edwards in modern times.

These guys were all ahead of the curve.

Throughout the 128-year history of West Virginia football, the Mountaineers have had some innovative coaches as well who set themselves apart from others.

Over the next four weeks, we will profile four of them, beginning today with Clarence Spears.

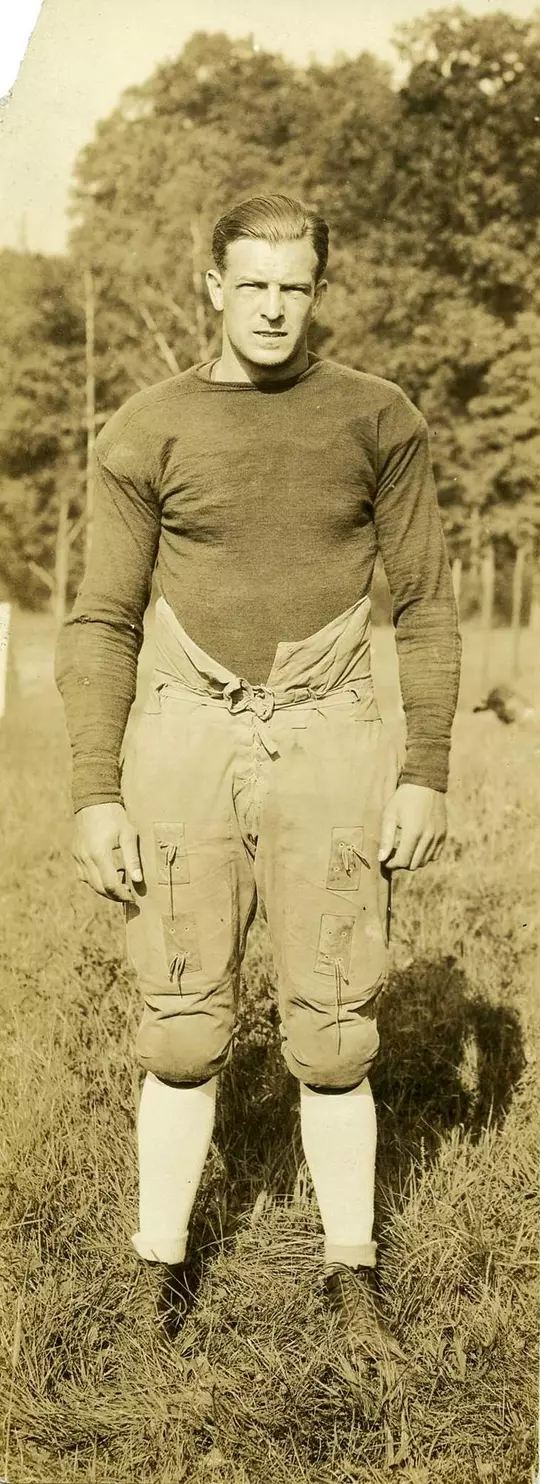

Doc Spears, as he was known at West Virginia during the early 1920s because he was also a practicing medical doctor, was exposed to the shift offense when he starred for Frank Cavanaugh at Dartmouth in 1914-15. Cavanaugh employed a unique version of the shift at Dartmouth that he passed on to Jack Marks, who then passed on to Knute Rockne at Notre Dame in the 1920s.

The Notre Dame Shift, as it was then known, stressed speed, deception and intelligence. Just before the ball was snapped, Notre Dame backfield players would move from their normal T-formation with the quarterback standing behind the center and two backs on each side, to a box formation to create confusion with reverses, misdirection plays, cross bucks and downfield passes.

Unlike the Minnesota Shift, which also included linemen moving in unison with the backfield to create an unbalanced line, the Notre Dame Shift was almost always done out of a balanced formation.

The basic concept of the shift was to create advantages by outflanking the opposition right before the football was put in play. The blockers required for this system had to be nimble and agile enough to move quickly, and to also be athletic enough to remain on their feet to block additional defenders down field.

Usually, the blocking was done from angles instead of straight-on.

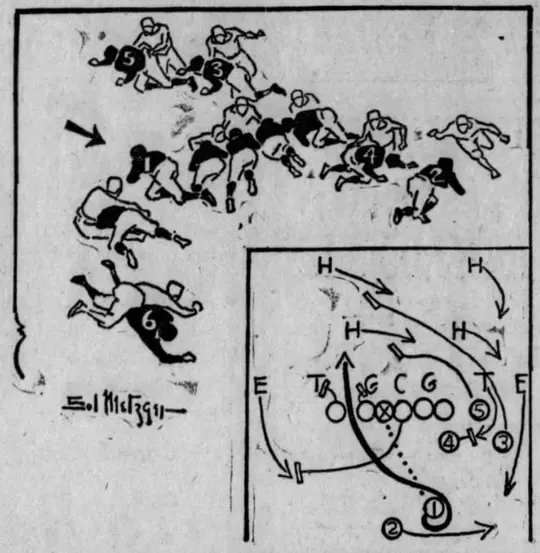

This was the version of the shift that Spears brought to West Virginia in 1921, as described by Sol Metzger in 1927.

“Spears’ Shift lands his team into a formation similar to Pop Warner’s, the rear backs being some 4 to 4 ½ yards back off the line. There are various plays possible – power plays, reverses, end runs and passes,” Metzger wrote. “But Spears has taken advantage of this to fool opponents.”

Metzger diagrammed one specific play where Spears had the lead back bluff a move to his right, pivot, and then head in the opposite direction to block the backside tackle with the ball carrier behind him.

What Metzger had diagrammed in 1927 was the modern-day counter play.

Upon taking the West Virginia job, Spears made his presence felt immediately. Spears’ players were required to run 25 minutes before assembling for breakfast during training camp at Jackson’s Mill and only three of them – guards Bill Johnson, Red Mahan and James Quinlan – weighed more than 200 pounds.

Spears’ best blocker was 190-pound Carl Davis from Charleston.

This is somewhat ironic considering the DeWitt, Arkansas, native weighed well more than 300 pounds when he coached at West Virginia!

And while he advocated running and conditioning, his practices were limited to just one scrimmage per week on Tuesdays during the season.

“We had little full-powered body contact,” Spears recalled in 1957. “The idea was to keep the timing sharp.”

We had little full-powered body contact. The idea was to keep the timing sharp.-- Clarence Spears, 1957

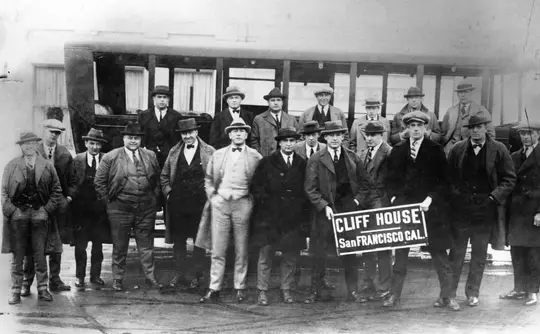

The Spears Shift came into form during his second season in 1922 when his players had gotten more familiar with it. West Virginia stunned Pitt 9-6 in Pittsburgh for its first victory over the Panthers in 19 years, and the Mountaineers also had impressive triumphs over Rutgers, Indiana, Virginia and Washington & Jefferson to earn an invitation to play Gonzaga in the East-West Bowl in San Diego.

Gonzaga’s Gus Dorais, a star player at Notre Dame for Rockne, was also considered one of the game’s bright young coaches before he moved on to the pro ranks. West Virginia jumped out to an early 21-0 lead over the Bulldogs and held on for a 21-13 victory to cap a 10-0-1 season.

Spears’ success continued in 1923 and 1924.

West Virginia defeated Pitt for a second consecutive year in 1923 and also topped Rutgers at the Polo Grounds in New York City and tied Penn State at Yankee Stadium.

An opportunity to go to the Rose Bowl ended in the mud in Morgantown on Thanksgiving Day when Washington & Jefferson upset WVU 7-2.

The great John Heisman, who coached the Presidents that season, recalled in 1928 his team’s unforgettable upset victory over the Mountaineers that afternoon.

After the 2007 loss at Pitt, the 1923 home defeat to Washington & Jefferson would be in contention for the second most stinging loss in school history considering what was at stake.

“The Mountaineers have just won 20 straight – one tie in the lot. They have a great team working ‘Tubby Spears’ Dartmouth Shift to perfection. The field is muddier than any hog-wallow, and rain is still pouring,” Heisman wrote. “We decided none of our carefully designed and practiced plays can go in such mud – nothing to do but watch the defense and punt and await our chance (doesn’t this sound eerily familiar to the 2007 Pitt game?).

“We do that very thing – get under their shift to stop it, then punt and keep this up,” he continued. “West Virginia fumbles at least 10 times in the game (seven, actually) – that’s because she’s taking chances trying to run that wet ball. (Washington & Jefferson) never fumbles the whole game and at last, they fumble again close to their goal line and this time we get it and run it over for the only touchdown of the game.”

Another narrow loss, this one 14-7 to Pitt at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, kept West Virginia from experiencing perfection once again in 1924. The Mountaineers concluded the ’24 season outscoring Colgate, Washington & Lee and Washington & Jefferson by a combined margin of 80-9 to end the year with an 8-1 record.

Spears also avenged the 1923 W&J defeat by routing the Presidents 40-7 in one of his most impressive victories at West Virginia.

WVU outscored its opponents 845-123 and posted a 25-2-2 record over Spears’ final three seasons at West Virginia in 1922, 1923 and 1924. Overall, his four-year winning percentage of .808 still ranks as the best in school history.

“Doc Spears had such great teams back in that day that he could have easily been elected governor,” West Virginia player Phil Hill said in 1957. “As a matter of fact, we tried to get him to run.”

The shift offenses West Virginia and Notre Dame were running in the mid-1920s had become so lethal that rules were changed to prohibit teams from moving before the ball was snapped.

In 1924, the football rules committee declared that on shift plays, players were required to come to an absolute stop and remain stationary momentarily. Three years later, “momentarily” was changed to a “one-second pause” before the ball was snapped.

Soon afterward, the shift lost its allure as more teams began transitioning to the T-formation.

Nevertheless, famed Pittsburgh sportswriter Chet Smith regarded Spears as one of college football’s “five-best coaches” in the mid-1920s when Spears left West Virginia for Minnesota.

Spears never won more than six games during his five seasons at Minnesota, and when he returned to the Big Ten following a two-year stint at Oregon, his coaching tenure at Wisconsin ended unceremoniously in 1935 when he was accused of giving his players whiskey during halftime of games and forcing injured players to suit up when the Badgers faced their biggest rivals.

Spears coached nine more seasons - seven at Toledo and two at Maryland - returning to West Virginia twice in 1937 and 1943 and losing on both occasions.

At each place Spears coached, he eventually encountered friction with athletic administrators.

“Spears was a fighter,” Minneapolis Star’s Charles Johnson wrote in 1964. “He could be very belligerent. He never ducked an argument. On the field, he was a driver who showed his athletes no mercy in drills trying to improve them, but he did well. Underneath, he had a soft spot, always fighting for the best interests of his gridders.”

Spears’ final record in 28 seasons as a collegiate head coach was 148-83-14. He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame as a player in 1955.

“If a team has a good grasp on the sound fundamentals of football it won’t have to worry much about the things the other team will do,” Spears once remarked.

He died in Jupiter, Florida, on Feb. 1, 1964.

Stay tuned for another Mountaineer football innovator next Sunday.