Photo by: WVU Athletic Communications

WVU’s Nehlen Explains 5 Iconic Mountaineer Football Plays

April 10, 2020 12:36 PM | Football, Blog

MORGANTOWN, W.Va. – Most of us have heard these calls before.

West Virginia lined up to go. There's a fake, Hostetler keeps the ball and goes around the right side into the end zone …

And the handoff given to Randolph with blockers, SWINGS OUT TO THE RIGHT, cuts down over the 20 …

Here is Harris in trouble, stiff arms a would-be tackler, COMES DOWN OVER THE 25, THE 20 …

Kelchner hands it off to Walker, WALKER GOES THROUGH THE LEFT SIDE …

Zereoue breaks over the left side, LOOK AT HIM GO. LOOK OUT, THEY'RE NOT GOING TO CATCH HIM …

Memorable West Virginia University football plays, for sure, made even more memorable because it was Jack Fleming describing them.

Years ago, there was a book published called The Golden Voices of Football, which chronicled the greatest play-by-play announcers in college football history. On page 143, sandwiched between Dick Enberg and Marty Glickman, was Jack Fleming.

Years ago, there was a book published called The Golden Voices of Football, which chronicled the greatest play-by-play announcers in college football history. On page 143, sandwiched between Dick Enberg and Marty Glickman, was Jack Fleming.

In the days before television and the internet, Fleming's tone and inflection during football games set the mood for an entire state. When Jack was excited, we were excited. When Jack was upset, we were upset. And when Jack turned reflective, so did we.

Many of Jack's most popular calls have since been recycled in video clips, re-aired on radio broadcasts or posted online.

Our Grant Dovey has revived the Jack Fleming website with all of Jack's most memorable clips, which can be found right here, and starting today, Mountaineer Sports Properties is introducing Fleming Fridays on social media to take us into June.

For those of us old enough to remember them, many of these iconic Mountaineer plays have become permanently embedded in our brains, thanks to Jack's brilliance.

But what made them so successful?

Why were they called?

Why were they called?

For that, we must turn to the person who originated many of them – Hall of Fame coach Don Nehlen.

Late last week, I caught up with a self-quarantining Nehlen at his home in Morgantown to go over a handful of the most memorable ones.

What did he see that made him call the play?

What went right to make it successful?

Coach gives us the answers.

So to borrow a phrase made popular by the late Paul Harvey ... And now, the rest of the story!

1983 Pitt: Jeff Hostetler's 6-yard touchdown run with 6:27 left in the game to give West Virginia a 24-21 lead

Anyone younger than 45 today has a difficult time comprehending how good Pitt was back in the late 1970s and early 1980s – think Alabama or Clemson good.

That's how talented the Panthers were then!

People around here used to joke that the Pitt players took a pay cut when they got to the NFL, especially when Jackie Sherrill was running the Panther program, but it was no laughing matter whenever West Virginia and Pitt lined up to play football games.

From 1976 until 1980, when Don Nehlen took over WVU football, the two programs were on two ends of the college football spectrum – Pitt at the top and West Virginia near the bottom.

But Nehlen closed the gap quickly. He almost got the Panthers up in Pittsburgh in 1982 before his team eventually ran out of gas, and in 1983 he finally had a football team physically capable of going toe-to-toe with Pitt.

But Nehlen closed the gap quickly. He almost got the Panthers up in Pittsburgh in 1982 before his team eventually ran out of gas, and in 1983 he finally had a football team physically capable of going toe-to-toe with Pitt.

When West Virginia took possession of the football at its own 10-yard line with 12:27 left in the game, the Mountaineers were trailing 21-17.

In the next six minutes, West Virginia methodically marched down the field in small chunks of yardage – never going backwards. No gimmicks. No tricks. It was Nehlen's guys running the football right down Pitt's throat.

"We drove the ball 90 yards for that score, and we converted, I think, two fourth-down situations," Nehlen recalled.

He also called just three pass plays, two of which Hostetler kept the football and scrambled for first-down runs.

When West Virginia had reached the Pitt 6-yard line, and the roar in the stadium could be heard all the way into Westover, Nehlen called Hostetler over to the sideline.

The coach had an idea.

He knew Pitt coach Foge Fazio loved to bring pressure, and he knew if he called 36, a dive play to fullback Ron Wolfley that Nehlen preferred to use near the goal line, Fazio would have eight guys in the box ready to stop Wolfley.

So this situation called for a little freelancing, which Nehlen rarely ever did – especially in big games.

He told Hoss to run 36, but instead of handing it off to Wolfley, keep it on a bootleg.

"You won't believe this, but we didn't even have that play," Nehlen said. "On the goal line, back then, we were a full-house team with a quarterback, a fullback behind him and a left and right halfback and our best play on the goal line was 36, which was Ronnie Wolfley running off tackle.

"We had done that a hundred times, and I knew that Pitt knew it as well as we did," Nehlen said. "I told Jeff, 'Keep the ball' and he just walked into the end zone. They had 9,000 guys going to tackle Ronnie, and Jeff just executed it perfectly."

The perfect play?

It was for that situation.

"If I remember correctly, nobody else on the team knew about it," Nehlen said.

Including freshman running back Pat Randolph, who made the key block at the 2 to spring Hoss into the end zone!

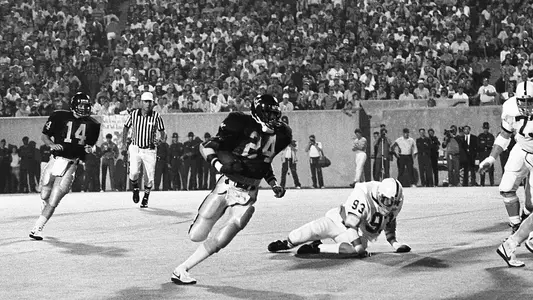

1984 Penn State: Pat Randolph's 22-yard touchdown run with 11:59 left in the fourth quarter to give WVU a 17-7 lead

All-America offensive tackle Brian Jozwiak swears Don Nehlen called Pat Randolph's go-ahead touchdown run the night before in the hotel ballroom after the players were finished watching their team movie.

With the lights still off, Nehlen walked up to the podium and flicked on the little reading light so the players could only see the outline of his face. He then began to go through the entire game, how both teams were going to have to fight, scratch and claw for every yard.

In the fourth quarter was when West Virginia was finally going to beat Penn State for the first time in 28 years, he said. They were going to run 58, Scottie Barrows was going to swing around and wipe out the safety and Pat Randolph was going to follow him right into the end zone.

And then, Woody (place kicker Paul Woodside) was going to seal the deal!

"Nehlen's brilliance," Jozwiak once recalled, "was that everything he said or did was pre-calculated and pre-planned. It was never on a whim."

Nehlen doesn't specifically recall spelling things out like that to his players, but he did admit he was big into visualization techniques back then.

"Well, that's great if they remembered that," he laughed. "At least I did something right."

What Nehlen remembers is the play being executed beautifully. West Virginia's John Moses had recovered a Penn State fumble at the Nittany Lion 39 and two runs got the ball to the 22.

Here, Nehlen decided to switch things up and go into an unbalanced line. The alignment was called "Bingo Right."

On the sweep, backside guard Scott Barrows was required to pull across to the strong side and block the uncovered safety.

The key was having a big guard who was nimble enough to get to the other side to make the play work, and Barrows was athletic enough to pull it off.

"We had about 10 total plays that were really part of our package every week, we might add or subtract something, but that was our base of plays," Nehlen said. "We camouflaged that play a little bit by the formation. I don't remember exactly how we got around the end so easily, but Scottie Barrows was about 280 pounds and that poor defensive back was in trouble because Scottie just ran him over!"

The perfect play?

It was in that situation.

"It was very, very well done," Nehlen said. "One of the great things about not having a lot of plays, but being very, very efficient in how you run them, is that we ran 58 over and over and over. We tried to confuse the defense a little bit by running it out of different looks, but 58 to the guards, center, tackles and the tight end was still 58. They didn't care about the motion going on behind them, and there isn't any question that play was as well executed as probably any play we ever called."

1988 Penn State – Major Harris 26-yard touchdown run on the opening possession of the game

There is perhaps no play more talked about by long-time West Virginia football fans than Major Harris' 26-yard touchdown run on opening possession of the Mountaineers' 51-30 victory over Penn State in 1988.

What made Major's run so remarkable was the fact that he went the wrong way. Nehlen called 37 and Harris ran 36, which meant 10 of his teammates were going to the left when he was going to the right.

That's never a good thing, especially when you are playing Penn State.

A funny story I once heard years later may shed some light on Harris' amazing run. It was said that the Penn State players were so smart and so well-schooled in their assignments that they knew West Virginia's plays better than the West Virginia players did.

Years ago, a former WVU tight end told me just as he once got down into his stance ready to run a play against Penn State he heard one of the Nittany Lion linebackers calling out the exact play they were about to run.

"I'm in my stance thinking, 'What the hell do we do now?'" he laughed.

So by Major going the wrong way it actually worked out well because there were nine Penn State defenders flying to the left where Harris was supposed to go, leaving Major with just two defenders to juke to the other side of the field.

So by Major going the wrong way it actually worked out well because there were nine Penn State defenders flying to the left where Harris was supposed to go, leaving Major with just two defenders to juke to the other side of the field.

And two-to-one odds for Harris out in the open is like stealing candy from a baby.

"There isn't any question we called 37 and Major ran 36 and everybody on the team ran 37," Nehlen said. "Penn State busted their butts to stop 37 and Major said, 'Oh my God, I've still got the ball.'

"He took off the other way and there were still a few guys left and he juked two or three of them and took it into the end zone," Nehlen said. "I remember he came off the field and he said, 'Coach, I'm sorry I thought I called 36.' I said to myself, 'Oh brother.' Then I told him, 'Don't worry about it, we'll take the results.'"

Nehlen added, "That was amazing, to be honest. Major had such talent. Once he got going north and south he was pretty darn good."

Later in the second quarter, right before halftime, Nehlen was content to call a draw play to run out the clock and take a 34-8 lead into the locker room at halftime.

You know, those draw plays that Nehlen seldom ever called.

"Don't ever ask me why they did it – I don't know what they thought we were going to do – but they blitzed their corner from the wide side of the field," Nehlen said. "Had they not blitzed we had nobody to block him. So we ran a draw play with Undra Johnson and my blockers are backing up to pass protect and as soon as the ball was snapped I said to myself, 'We've got a chance to pop this thing' because I saw their corner coming. He was running south and Undra had the ball running north."

Johnson was also the perfect guy to have on the field to run that play because he was much, much faster than West Virginia's other two running backs, A.B. Brown or Eugene Napoleon.

Undra had the straight-line speed capable of taking it to the house, which he did.

Later, some accused Nehlen of running up the score when all he was simply doing was running out the clock.

"They were great pass rushers, and I know I got criticized a lot for running the draw, but that one worked," he said.

"If you go back over my 21 years and cut out every draw play, who knows what we would have averaged because it was a big, big play for us," Nehlen explained. "We ran the play, not so much to pop it, but because we played great defense. If it didn't work, we punted the ball and we knew we were going to get it back in lieu of making a mistake and throwing it to the other guys."

1993 Miami – Robert Walker's 19-yard touchdown run with 6:08 remaining in the game to give West Virginia a 17-14 lead

Miami had a little outside linebacker named Rohan Marley, the son of famous reggae singer Bob Marley. Rohan was a terrific football player, but he was extremely small for his position, listed at 5-feet-8 and 205 pounds.

He might have been 5-8, but the 205 pounds were extremely generous.

After studying tape of the Hurricanes all week, Don Nehlen knew his football team was going to have to slug it out with Miami, which had a great defense with Warren Sapp controlling the line of scrimmage and a young dude named Ray Lewis backing up regular inside linebackers Robert Bass and Corwin Francis.

But the Canes were just an average offensive football team that year, which meant the game was going to resemble more of a siege than an incursion.

So Nehlen decided that he was going to run the ball behind his best football player, left tackle Rich Braham. He wanted to pound that little guy, and pound him, and pound him some more.

Eventually, Marley was going to get tired.

That moment came with six minutes left in a football game West Virginia was trailing 14-10. The play Nehlen called was 43.

But this time Marley wasn't in the game, the result of an injury. In his place was backup James Burgess.

"Don't misunderstand me because the kid was a very good player, but we just kept running that play and running that play. The linebacker has to take the blocker on properly, and by that I mean he has to take him on with his inside shoulder so that the ball will flow back to the inside where the backside backer and the backside tackle can help him," Nehlen explained.

"Don't misunderstand me because the kid was a very good player, but we just kept running that play and running that play. The linebacker has to take the blocker on properly, and by that I mean he has to take him on with his inside shoulder so that the ball will flow back to the inside where the backside backer and the backside tackle can help him," Nehlen explained.

"Anyway, we kept pounding him and all of a sudden the guy in there made a mistake and took him on with his outside shoulder and that opened up a seam. Robert had the quickness to pop through that seam and just outrun the secondary and take it into the end zone," Nehlen said.

On the play, Braham took care of the defensive end at the line of scrimmage, guard Tom Robsock got the inside seal and fullback Rodney Woodward blocked Burgess filling the hole.

The play covered just 19 yards, but in a game like that when everything was confined to such a small area of the football field, it seemed like 70 yards.

"We ran it a lot in that game and a lot of times it gained 2, 3 or 4 yards, but the great thing about a team that can run the football is in the fourth quarter they become very dominant," Nehlen said.

Nehlen was also smart enough to run behind Braham, who was clearly his best football player and one of the most underrated football players in school history, in Nehlen's opinion.

"Here was a guy nobody recruited, I'm talking nobody," the coach marveled. "And he became a great, great football player."

1996 Pitt – Freshman Amos Zereoue's 69-yard touchdown run on the very first carry of his college football career

As a matter of full disclosure, Pitt was horrible in 1996. Back to the Future with Johnny Majors in the mid-1990s was an abject failure, and Majors' second go-around with the Panthers was already petering out in '96.

You could tell right away on West Virginia's opening series of the game that another can of Panther whup-ass was about to be opened.

With 10 minutes showing on the game clock, Nehlen called 43 – the same play Robert Walker scored the go-ahead touchdown to beat Miami in 1993 – with his little freshman running back Amos Zereoue carrying the ball.

Amos may have been short, but he was powerfully built with great elusiveness and outstanding straight-line speed.

Normally, 43 is run out of an I backfield formation with the fullback leading the tailback into the hole, but this time Zereoue was lined up in a split backfield formation.

"We very, very seldom ever did that because it puts the back in a little bit of a disadvantage," Nehlen explained. "From the I formation you line that tailback up about 7 ½ yards from the line of scrimmage and he has the ability to go straight ahead, bounce it left or bounce it right and when you bring them across in a split-back formation like we did there with Amos or out of these shot-gun formations, they get the ball and they are running parallel to the line of scrimmage and it makes it hard to cut."

Fortunately for West Virginia, Pitt's defense was not properly aligned, which created a huge opening for Zereoue to run through.

"Amos didn't have to cut because the defensive tackle just shot down across the face of our tackle and our tackle took him out and the lead back was running down the field trying to find someone to block," Nehlen said. "He couldn't find anybody so Amos just ran past him to the end zone.

"We never did it very much because it's not a great way to run that play, and I don't even remember why we did it, but we did," he said. "The play was effective because their defense was so bad, to be honest about it."

Sixty-nine yards later, Amos Zereoue had his first college touchdown – on his first-ever carry.

Sixty-nine yards later, Amos Zereoue had his first college touchdown – on his first-ever carry.

What an amazing turn of events!

In 1981, when Pitt quarterback Dan Marino was injured, the Panthers put in a defensive back to play quarterback and threw the ball just six times to beat West Virginia 17-0.

That's because West Virginia couldn't move the ball past the 50-yard line against the Panthers.

Fifteen years later, Nehlen had completely flipped the football series in West Virginia's favor.

"It's amazing because when I got here Pitt was the best team in the country, no question about it," Nehlen said. "They had more football players than anybody in the country. But after we got on the same playing field that they were on we pretty much dominated Pittsburgh.

"When it was an uneven playing field we struggled, and to think we caught that outfit in just three years is absolutely amazing," he said.

It was amazing.

And now you know the rest of the story!

Happy Easter everyone!

West Virginia lined up to go. There's a fake, Hostetler keeps the ball and goes around the right side into the end zone …

And the handoff given to Randolph with blockers, SWINGS OUT TO THE RIGHT, cuts down over the 20 …

Here is Harris in trouble, stiff arms a would-be tackler, COMES DOWN OVER THE 25, THE 20 …

Kelchner hands it off to Walker, WALKER GOES THROUGH THE LEFT SIDE …

Zereoue breaks over the left side, LOOK AT HIM GO. LOOK OUT, THEY'RE NOT GOING TO CATCH HIM …

Memorable West Virginia University football plays, for sure, made even more memorable because it was Jack Fleming describing them.

Years ago, there was a book published called The Golden Voices of Football, which chronicled the greatest play-by-play announcers in college football history. On page 143, sandwiched between Dick Enberg and Marty Glickman, was Jack Fleming.

Years ago, there was a book published called The Golden Voices of Football, which chronicled the greatest play-by-play announcers in college football history. On page 143, sandwiched between Dick Enberg and Marty Glickman, was Jack Fleming.In the days before television and the internet, Fleming's tone and inflection during football games set the mood for an entire state. When Jack was excited, we were excited. When Jack was upset, we were upset. And when Jack turned reflective, so did we.

Many of Jack's most popular calls have since been recycled in video clips, re-aired on radio broadcasts or posted online.

Our Grant Dovey has revived the Jack Fleming website with all of Jack's most memorable clips, which can be found right here, and starting today, Mountaineer Sports Properties is introducing Fleming Fridays on social media to take us into June.

For those of us old enough to remember them, many of these iconic Mountaineer plays have become permanently embedded in our brains, thanks to Jack's brilliance.

But what made them so successful?

Why were they called?

Why were they called?For that, we must turn to the person who originated many of them – Hall of Fame coach Don Nehlen.

Late last week, I caught up with a self-quarantining Nehlen at his home in Morgantown to go over a handful of the most memorable ones.

What did he see that made him call the play?

What went right to make it successful?

Coach gives us the answers.

So to borrow a phrase made popular by the late Paul Harvey ... And now, the rest of the story!

1983 Pitt: Jeff Hostetler's 6-yard touchdown run with 6:27 left in the game to give West Virginia a 24-21 lead

Anyone younger than 45 today has a difficult time comprehending how good Pitt was back in the late 1970s and early 1980s – think Alabama or Clemson good.

That's how talented the Panthers were then!

People around here used to joke that the Pitt players took a pay cut when they got to the NFL, especially when Jackie Sherrill was running the Panther program, but it was no laughing matter whenever West Virginia and Pitt lined up to play football games.

From 1976 until 1980, when Don Nehlen took over WVU football, the two programs were on two ends of the college football spectrum – Pitt at the top and West Virginia near the bottom.

But Nehlen closed the gap quickly. He almost got the Panthers up in Pittsburgh in 1982 before his team eventually ran out of gas, and in 1983 he finally had a football team physically capable of going toe-to-toe with Pitt.

But Nehlen closed the gap quickly. He almost got the Panthers up in Pittsburgh in 1982 before his team eventually ran out of gas, and in 1983 he finally had a football team physically capable of going toe-to-toe with Pitt.When West Virginia took possession of the football at its own 10-yard line with 12:27 left in the game, the Mountaineers were trailing 21-17.

In the next six minutes, West Virginia methodically marched down the field in small chunks of yardage – never going backwards. No gimmicks. No tricks. It was Nehlen's guys running the football right down Pitt's throat.

"We drove the ball 90 yards for that score, and we converted, I think, two fourth-down situations," Nehlen recalled.

He also called just three pass plays, two of which Hostetler kept the football and scrambled for first-down runs.

When West Virginia had reached the Pitt 6-yard line, and the roar in the stadium could be heard all the way into Westover, Nehlen called Hostetler over to the sideline.

The coach had an idea.

He knew Pitt coach Foge Fazio loved to bring pressure, and he knew if he called 36, a dive play to fullback Ron Wolfley that Nehlen preferred to use near the goal line, Fazio would have eight guys in the box ready to stop Wolfley.

So this situation called for a little freelancing, which Nehlen rarely ever did – especially in big games.

He told Hoss to run 36, but instead of handing it off to Wolfley, keep it on a bootleg.

"You won't believe this, but we didn't even have that play," Nehlen said. "On the goal line, back then, we were a full-house team with a quarterback, a fullback behind him and a left and right halfback and our best play on the goal line was 36, which was Ronnie Wolfley running off tackle.

"We had done that a hundred times, and I knew that Pitt knew it as well as we did," Nehlen said. "I told Jeff, 'Keep the ball' and he just walked into the end zone. They had 9,000 guys going to tackle Ronnie, and Jeff just executed it perfectly."

The perfect play?

It was for that situation.

"If I remember correctly, nobody else on the team knew about it," Nehlen said.

Including freshman running back Pat Randolph, who made the key block at the 2 to spring Hoss into the end zone!

1984 Penn State: Pat Randolph's 22-yard touchdown run with 11:59 left in the fourth quarter to give WVU a 17-7 lead

All-America offensive tackle Brian Jozwiak swears Don Nehlen called Pat Randolph's go-ahead touchdown run the night before in the hotel ballroom after the players were finished watching their team movie.

With the lights still off, Nehlen walked up to the podium and flicked on the little reading light so the players could only see the outline of his face. He then began to go through the entire game, how both teams were going to have to fight, scratch and claw for every yard.

In the fourth quarter was when West Virginia was finally going to beat Penn State for the first time in 28 years, he said. They were going to run 58, Scottie Barrows was going to swing around and wipe out the safety and Pat Randolph was going to follow him right into the end zone.

And then, Woody (place kicker Paul Woodside) was going to seal the deal!

"Nehlen's brilliance," Jozwiak once recalled, "was that everything he said or did was pre-calculated and pre-planned. It was never on a whim."

Nehlen doesn't specifically recall spelling things out like that to his players, but he did admit he was big into visualization techniques back then.

"Well, that's great if they remembered that," he laughed. "At least I did something right."

What Nehlen remembers is the play being executed beautifully. West Virginia's John Moses had recovered a Penn State fumble at the Nittany Lion 39 and two runs got the ball to the 22.

Here, Nehlen decided to switch things up and go into an unbalanced line. The alignment was called "Bingo Right."

On the sweep, backside guard Scott Barrows was required to pull across to the strong side and block the uncovered safety.

The key was having a big guard who was nimble enough to get to the other side to make the play work, and Barrows was athletic enough to pull it off.

"We had about 10 total plays that were really part of our package every week, we might add or subtract something, but that was our base of plays," Nehlen said. "We camouflaged that play a little bit by the formation. I don't remember exactly how we got around the end so easily, but Scottie Barrows was about 280 pounds and that poor defensive back was in trouble because Scottie just ran him over!"

The perfect play?

It was in that situation.

"It was very, very well done," Nehlen said. "One of the great things about not having a lot of plays, but being very, very efficient in how you run them, is that we ran 58 over and over and over. We tried to confuse the defense a little bit by running it out of different looks, but 58 to the guards, center, tackles and the tight end was still 58. They didn't care about the motion going on behind them, and there isn't any question that play was as well executed as probably any play we ever called."

1988 Penn State – Major Harris 26-yard touchdown run on the opening possession of the game

There is perhaps no play more talked about by long-time West Virginia football fans than Major Harris' 26-yard touchdown run on opening possession of the Mountaineers' 51-30 victory over Penn State in 1988.

What made Major's run so remarkable was the fact that he went the wrong way. Nehlen called 37 and Harris ran 36, which meant 10 of his teammates were going to the left when he was going to the right.

That's never a good thing, especially when you are playing Penn State.

A funny story I once heard years later may shed some light on Harris' amazing run. It was said that the Penn State players were so smart and so well-schooled in their assignments that they knew West Virginia's plays better than the West Virginia players did.

Years ago, a former WVU tight end told me just as he once got down into his stance ready to run a play against Penn State he heard one of the Nittany Lion linebackers calling out the exact play they were about to run.

"I'm in my stance thinking, 'What the hell do we do now?'" he laughed.

So by Major going the wrong way it actually worked out well because there were nine Penn State defenders flying to the left where Harris was supposed to go, leaving Major with just two defenders to juke to the other side of the field.

So by Major going the wrong way it actually worked out well because there were nine Penn State defenders flying to the left where Harris was supposed to go, leaving Major with just two defenders to juke to the other side of the field.And two-to-one odds for Harris out in the open is like stealing candy from a baby.

"There isn't any question we called 37 and Major ran 36 and everybody on the team ran 37," Nehlen said. "Penn State busted their butts to stop 37 and Major said, 'Oh my God, I've still got the ball.'

"He took off the other way and there were still a few guys left and he juked two or three of them and took it into the end zone," Nehlen said. "I remember he came off the field and he said, 'Coach, I'm sorry I thought I called 36.' I said to myself, 'Oh brother.' Then I told him, 'Don't worry about it, we'll take the results.'"

Nehlen added, "That was amazing, to be honest. Major had such talent. Once he got going north and south he was pretty darn good."

Later in the second quarter, right before halftime, Nehlen was content to call a draw play to run out the clock and take a 34-8 lead into the locker room at halftime.

You know, those draw plays that Nehlen seldom ever called.

"Don't ever ask me why they did it – I don't know what they thought we were going to do – but they blitzed their corner from the wide side of the field," Nehlen said. "Had they not blitzed we had nobody to block him. So we ran a draw play with Undra Johnson and my blockers are backing up to pass protect and as soon as the ball was snapped I said to myself, 'We've got a chance to pop this thing' because I saw their corner coming. He was running south and Undra had the ball running north."

Johnson was also the perfect guy to have on the field to run that play because he was much, much faster than West Virginia's other two running backs, A.B. Brown or Eugene Napoleon.

Undra had the straight-line speed capable of taking it to the house, which he did.

Later, some accused Nehlen of running up the score when all he was simply doing was running out the clock.

"They were great pass rushers, and I know I got criticized a lot for running the draw, but that one worked," he said.

"If you go back over my 21 years and cut out every draw play, who knows what we would have averaged because it was a big, big play for us," Nehlen explained. "We ran the play, not so much to pop it, but because we played great defense. If it didn't work, we punted the ball and we knew we were going to get it back in lieu of making a mistake and throwing it to the other guys."

1993 Miami – Robert Walker's 19-yard touchdown run with 6:08 remaining in the game to give West Virginia a 17-14 lead

Miami had a little outside linebacker named Rohan Marley, the son of famous reggae singer Bob Marley. Rohan was a terrific football player, but he was extremely small for his position, listed at 5-feet-8 and 205 pounds.

He might have been 5-8, but the 205 pounds were extremely generous.

After studying tape of the Hurricanes all week, Don Nehlen knew his football team was going to have to slug it out with Miami, which had a great defense with Warren Sapp controlling the line of scrimmage and a young dude named Ray Lewis backing up regular inside linebackers Robert Bass and Corwin Francis.

But the Canes were just an average offensive football team that year, which meant the game was going to resemble more of a siege than an incursion.

So Nehlen decided that he was going to run the ball behind his best football player, left tackle Rich Braham. He wanted to pound that little guy, and pound him, and pound him some more.

Eventually, Marley was going to get tired.

That moment came with six minutes left in a football game West Virginia was trailing 14-10. The play Nehlen called was 43.

But this time Marley wasn't in the game, the result of an injury. In his place was backup James Burgess.

"Don't misunderstand me because the kid was a very good player, but we just kept running that play and running that play. The linebacker has to take the blocker on properly, and by that I mean he has to take him on with his inside shoulder so that the ball will flow back to the inside where the backside backer and the backside tackle can help him," Nehlen explained.

"Don't misunderstand me because the kid was a very good player, but we just kept running that play and running that play. The linebacker has to take the blocker on properly, and by that I mean he has to take him on with his inside shoulder so that the ball will flow back to the inside where the backside backer and the backside tackle can help him," Nehlen explained. "Anyway, we kept pounding him and all of a sudden the guy in there made a mistake and took him on with his outside shoulder and that opened up a seam. Robert had the quickness to pop through that seam and just outrun the secondary and take it into the end zone," Nehlen said.

On the play, Braham took care of the defensive end at the line of scrimmage, guard Tom Robsock got the inside seal and fullback Rodney Woodward blocked Burgess filling the hole.

The play covered just 19 yards, but in a game like that when everything was confined to such a small area of the football field, it seemed like 70 yards.

"We ran it a lot in that game and a lot of times it gained 2, 3 or 4 yards, but the great thing about a team that can run the football is in the fourth quarter they become very dominant," Nehlen said.

Nehlen was also smart enough to run behind Braham, who was clearly his best football player and one of the most underrated football players in school history, in Nehlen's opinion.

"Here was a guy nobody recruited, I'm talking nobody," the coach marveled. "And he became a great, great football player."

1996 Pitt – Freshman Amos Zereoue's 69-yard touchdown run on the very first carry of his college football career

As a matter of full disclosure, Pitt was horrible in 1996. Back to the Future with Johnny Majors in the mid-1990s was an abject failure, and Majors' second go-around with the Panthers was already petering out in '96.

You could tell right away on West Virginia's opening series of the game that another can of Panther whup-ass was about to be opened.

With 10 minutes showing on the game clock, Nehlen called 43 – the same play Robert Walker scored the go-ahead touchdown to beat Miami in 1993 – with his little freshman running back Amos Zereoue carrying the ball.

Amos may have been short, but he was powerfully built with great elusiveness and outstanding straight-line speed.

Normally, 43 is run out of an I backfield formation with the fullback leading the tailback into the hole, but this time Zereoue was lined up in a split backfield formation.

"We very, very seldom ever did that because it puts the back in a little bit of a disadvantage," Nehlen explained. "From the I formation you line that tailback up about 7 ½ yards from the line of scrimmage and he has the ability to go straight ahead, bounce it left or bounce it right and when you bring them across in a split-back formation like we did there with Amos or out of these shot-gun formations, they get the ball and they are running parallel to the line of scrimmage and it makes it hard to cut."

Fortunately for West Virginia, Pitt's defense was not properly aligned, which created a huge opening for Zereoue to run through.

"Amos didn't have to cut because the defensive tackle just shot down across the face of our tackle and our tackle took him out and the lead back was running down the field trying to find someone to block," Nehlen said. "He couldn't find anybody so Amos just ran past him to the end zone.

"We never did it very much because it's not a great way to run that play, and I don't even remember why we did it, but we did," he said. "The play was effective because their defense was so bad, to be honest about it."

Sixty-nine yards later, Amos Zereoue had his first college touchdown – on his first-ever carry.

Sixty-nine yards later, Amos Zereoue had his first college touchdown – on his first-ever carry.What an amazing turn of events!

In 1981, when Pitt quarterback Dan Marino was injured, the Panthers put in a defensive back to play quarterback and threw the ball just six times to beat West Virginia 17-0.

That's because West Virginia couldn't move the ball past the 50-yard line against the Panthers.

Fifteen years later, Nehlen had completely flipped the football series in West Virginia's favor.

"It's amazing because when I got here Pitt was the best team in the country, no question about it," Nehlen said. "They had more football players than anybody in the country. But after we got on the same playing field that they were on we pretty much dominated Pittsburgh.

"When it was an uneven playing field we struggled, and to think we caught that outfit in just three years is absolutely amazing," he said.

It was amazing.

And now you know the rest of the story!

Happy Easter everyone!

Rich Rodriguez | Dec. 3

Wednesday, December 03

Reid Carrico | Nov. 29

Saturday, November 29

Jeff Weimer | Nov. 29

Saturday, November 29

Rich Rodriguez | Nov. 29

Saturday, November 29