The 1918 Flu Pandemic Claimed WVU's Football Season

March 16, 2020 05:07 PM | Football, Blog

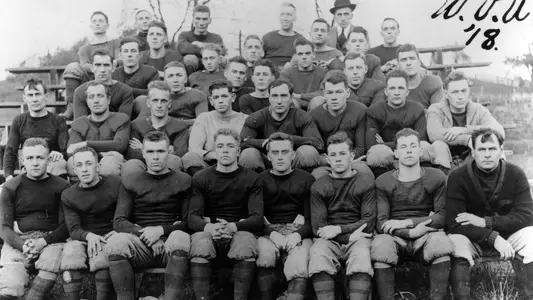

MORGANTOWN, W.Va. – It came quickly and forcefully. A crippling flu pandemic, which killed an estimated 20- to 50-million people worldwide, coupled with the United States' involvement in World War I, claimed West Virginia University's 1918 football season.

This is how William Doherty and Festus Summers characterized WVU's decision to cancel football in their definitive history of West Virginia University, West Virginia University: Symbol of Unity in a Sectionalized State, published in 1982: "In 1918, due to the influenza epidemic, the University did not attempt to field a football team."

That's not completely accurate.

West Virginia did try to field a football team and continued to try and play football almost right up until season's end, despite overwhelming odds. WVU was coming off a groundbreaking season in 1917 that included the school's first victory of national significance against Navy.

The undefeated Midshipmen that year were coached by Gilmour Dobie, whose 12-year winning streak spanned his coaching tenures at North Dakota Agricultural, Washington and Navy, and ended with the loss to West Virginia on Oct. 6, 1917, in Annapolis.

WVU won the game when it successfully pulled off a fake punt in the fourth quarter and Frank Harris ran 35 yards for a touchdown. Afterward, a distraught Dobie couldn't keep from weeping when he shook West Virginia co-head coach Mont McIntire's hand at midfield.

A boastful McIntire told Weston author Kent Kessler 42 years later in Kessler's book Hail West Virginians! that "nothing I said would have helped Dobie … he just didn't know what it felt like to lose!"

A boastful McIntire told Weston author Kent Kessler 42 years later in Kessler's book Hail West Virginians! that "nothing I said would have helped Dobie … he just didn't know what it felt like to lose!"

That Navy victory in 1917 was similar to Don Nehlen's back-to-back wins over Florida and Oklahoma in 1981-82, and Rich Rodriguez's triumph against Georgia in the 2006 Nokia Sugar Bowl in terms of the national perception of West Virginia University football.

WVU had become a hot commodity, and ambitious, young athletic director Harry Stansbury was going to capitalize on it.

The first thing Stansbury did soon after the calendar flipped to 1918 was remove the "co-head coach" tag from McIntire and place him in full charge of the football team. McIntire had been sharing the job with former Penn State gridder Elgie Tobin for two years before the decision was made not to renew Tobin's contract.

The United States' official involvement in World War I on April 6, 1917 was less than two months after McIntire's title change, and soon some of McIntire's best players were joining the U.S. war effort, most notably Huntington halfback Clay Hite.

Another conspicuous absence was All-America fullback Ira Errett Rodgers, but All-American center Russ Bailey, outstanding tackle Russ Meredith and left end Paul Dawson were returning from the 1917 squad.

To supplement the losses, McIntire managed to convince four key members of the 1917 West Virginia all-state team to attend West Virginia University – New Martinsville's Clem Kiger, Parkersburg's Joe Setron, Charleston's Homer Martin and Weston's Joseph Fuccy. Because of reduced student enrollment, freshmen ineligibility was waived for the duration of the war and Stansbury managed to get schools that he was negotiating games with to abrogate their freshman rule.

The big domino to fall was Nebraska, which Stansbury convinced to come to Morgantown to play West Virginia on Oct. 26.

The eight-game football schedule also included road games at Pitt, Army and Rutgers and a meeting with Michigan Agricultural (Michigan State) in Charleston. The campaign was to conclude on Thanksgiving Day in Fairmont against arch-rival Washington & Jefferson.

Stansbury was also still negotiating with Indiana to come to Morgantown on Nov. 9 at the time he released West Virginia's football schedule on Sept. 7.

This was the original 1918 Mountaineer football slate:

Oct. 5, Marietta

Oct. 12, at Pitt

Oct. 19, at Army

Oct, 26, Nebraska

Nov. 2, Michigan State (Charleston, W.Va.)

Nov. 16, at Rutgers

Nov. 23, Westminster

Nov. 28, Washington & Jefferson (Fairmont, W.Va.)

With H.P. Mullenex agreeing to assist McIntire on a temporary basis until the end of the war, West Virginia began practicing on Sept. 16 with a football squad consisting of 45 players. The vast majority of those guys were also part of the Student Army Training Corps (SATC), which was coordinated by the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) and was established through the National Defense Act of 1916 to help supplement the Army's shortage of officer candidates for the war effort.

The SATC was regulated by the U.S. War Department and participants were issued strict time parameters for specific areas of study. What it amounted to was a short window of less than three hours of free time for practice each day, with Saturdays open for games as long as players were back on campus by Sunday.

This proved a major obstacle for many teams, such as Pitt, which didn't have an on-site practice facility and used up a good portion of its time traveling to and from practice. Still, the Panthers were able to cobble together a five-game schedule in 1918 that included a 32-0 victory over Georgia Tech to earn it recognition as college football's national champion.

West Virginia's SATC players, for some reason, encountered much tighter time restrictions than their counterparts at Pitt, Penn State and other local schools, but McIntire forged ahead with preparations for the season nevertheless.

During one September scrimmage, the varsity team, led by halfback Jack Latterner, scored six touchdowns against the reserves and among the young players to emerge from that scrimmage were Martin, Kiger and Fuccy.

Those three were expected to be in West Virginia's starting lineup when the season opened on Saturday, Oct. 5 against Marietta.

Then, Philadelphia decided to have its Liberty Loan Parade on Sept. 28 despite a flu virus that was already overrunning the Philadelphia Navy Yard. More than 200,000 people attended that parade and soon the city became besieged with severe cases of the flu that ultimately resulted in more than 12,000 deaths in a six-week span.

The virus became known as the "Spanish Flu" because neutral Spain was the only country in the world to publicize its ravishing effects consuming the globe by the fall of 1918. Others, including the U.S., downplayed it because they didn't want to incite panic during wartime.

The virus had first shown up in the spring but died off during the summer before a more virulent mutation of it re-formed in the fall with far greater voracity. Cities such as St. Louis and San Francisco, which imposed draconian measures to limit social contact, were spared much of the carnage, while other cities such as Philadelphia and New York were not.

The virus had first shown up in the spring but died off during the summer before a more virulent mutation of it re-formed in the fall with far greater voracity. Cities such as St. Louis and San Francisco, which imposed draconian measures to limit social contact, were spared much of the carnage, while other cities such as Philadelphia and New York were not.

At any rate, the virus made its way to Morgantown in late September and caused the cancellation of the Marietta game. Especially hard hit was the SATC, requiring the immediate quarantine of West Virginia's 45-member football squad. It was hoped that the quarantine would be effective enough to save the Pitt game on Oct. 12, but it was cancelled the week of the contest and West Virginia's Committee on Education abruptly ordered students to leave campus and not return until the virus was contained.

While away from campus, promising tackle Joseph Fuccy developed a slight cold that he didn't take too seriously upon returning to Weston, according to an account published in the Oct. 20, 1918 edition of The Pittsburgh Press. Fuccy's influenza soon developed into pneumonia and he died quickly. This second wave of the virus turned out to be particularly lethal to 20- to 40-year-olds - normally an age group that fared much better against the flu.

Fuccy's sudden death cast a pall on the football season, but it didn't totally eliminate efforts to reconstitute a team when students returned to campus on Nov. 5.

In the meantime, the city of Morgantown ordered the closing of all theaters, churches and other public places of gathering when it had reached more than 200 flu cases by November, according to Doherty Jr. and Summers.

The football games scheduled in October against Army and Nebraska, as well as the early-November meeting with Michigan State in Charleston, were abandoned, but Stansbury hoped to play the final contests against Rutgers, Westminster and Washington & Jefferson.

The W&J game was particularly important to Stansbury because the Presidents regularly drew crowds of more than 10,000, and the game was extremely profitable to the University and local merchants.

Then came the announcement on Nov. 9, two days before Armistice Day, that West Virginia was officially canceling its football season. The reason given was not the crippling influenza outbreak, which ultimately claimed the lives of more than 650,000 U.S. citizens, but rather the enormous time constraints imposed on the players by the SATC.

The regular rhythms of campus life soon returned to Morgantown, and the WVU basketball team completed a full 17-game schedule in the winter of 1919, although it probably should have reconsidered since it won just four of those contests.

The WVU baseball team, under second-year coach Kemper Shelton, won 14 of its 18 games later that spring, and a reconstituted WVU football team, with all of its star players from the 1917 squad back in the fold, had an outstanding season in 1919 with an 8-2 record that included a big victory at Princeton.

Ira Rodgers became the school's first consensus All-American football player in 1919 and helped put WVU on a path toward the most successful period of football in school history when Dartmouth's Clarence Spears took over in 1921.

Ira Rodgers became the school's first consensus All-American football player in 1919 and helped put WVU on a path toward the most successful period of football in school history when Dartmouth's Clarence Spears took over in 1921.

The Football Review in 1944 listed West Virginia's grid teams of 1922, 1923, 1924 and 1925 among the nation's 10-best in the country – a consistent run of success approached only once since when Rich Rodriguez guided three Top 10 teams in 2005, 2006 and 2007.

Also, rising out of the ashes of that aborted 1918 football campaign was the construction of old Mountaineer Field, which officially opened in 1925 and served as the home for West Virginia University football until 1979.

Not even the most optimistic person living in Morgantown back in 1918 could have envisioned that ever happening when world war and a crippling influenza outbreak had grounded everyday life to a complete halt.

The lesson learned from what happened in 1918 applies to today's lethal strain of the COVID-19 virus that is systematically making its way across the country - limit your social contact to let this thing run its course!

This is how William Doherty and Festus Summers characterized WVU's decision to cancel football in their definitive history of West Virginia University, West Virginia University: Symbol of Unity in a Sectionalized State, published in 1982: "In 1918, due to the influenza epidemic, the University did not attempt to field a football team."

That's not completely accurate.

West Virginia did try to field a football team and continued to try and play football almost right up until season's end, despite overwhelming odds. WVU was coming off a groundbreaking season in 1917 that included the school's first victory of national significance against Navy.

The undefeated Midshipmen that year were coached by Gilmour Dobie, whose 12-year winning streak spanned his coaching tenures at North Dakota Agricultural, Washington and Navy, and ended with the loss to West Virginia on Oct. 6, 1917, in Annapolis.

WVU won the game when it successfully pulled off a fake punt in the fourth quarter and Frank Harris ran 35 yards for a touchdown. Afterward, a distraught Dobie couldn't keep from weeping when he shook West Virginia co-head coach Mont McIntire's hand at midfield.

A boastful McIntire told Weston author Kent Kessler 42 years later in Kessler's book Hail West Virginians! that "nothing I said would have helped Dobie … he just didn't know what it felt like to lose!"

A boastful McIntire told Weston author Kent Kessler 42 years later in Kessler's book Hail West Virginians! that "nothing I said would have helped Dobie … he just didn't know what it felt like to lose!"That Navy victory in 1917 was similar to Don Nehlen's back-to-back wins over Florida and Oklahoma in 1981-82, and Rich Rodriguez's triumph against Georgia in the 2006 Nokia Sugar Bowl in terms of the national perception of West Virginia University football.

WVU had become a hot commodity, and ambitious, young athletic director Harry Stansbury was going to capitalize on it.

The first thing Stansbury did soon after the calendar flipped to 1918 was remove the "co-head coach" tag from McIntire and place him in full charge of the football team. McIntire had been sharing the job with former Penn State gridder Elgie Tobin for two years before the decision was made not to renew Tobin's contract.

The United States' official involvement in World War I on April 6, 1917 was less than two months after McIntire's title change, and soon some of McIntire's best players were joining the U.S. war effort, most notably Huntington halfback Clay Hite.

Another conspicuous absence was All-America fullback Ira Errett Rodgers, but All-American center Russ Bailey, outstanding tackle Russ Meredith and left end Paul Dawson were returning from the 1917 squad.

To supplement the losses, McIntire managed to convince four key members of the 1917 West Virginia all-state team to attend West Virginia University – New Martinsville's Clem Kiger, Parkersburg's Joe Setron, Charleston's Homer Martin and Weston's Joseph Fuccy. Because of reduced student enrollment, freshmen ineligibility was waived for the duration of the war and Stansbury managed to get schools that he was negotiating games with to abrogate their freshman rule.

The big domino to fall was Nebraska, which Stansbury convinced to come to Morgantown to play West Virginia on Oct. 26.

The eight-game football schedule also included road games at Pitt, Army and Rutgers and a meeting with Michigan Agricultural (Michigan State) in Charleston. The campaign was to conclude on Thanksgiving Day in Fairmont against arch-rival Washington & Jefferson.

Stansbury was also still negotiating with Indiana to come to Morgantown on Nov. 9 at the time he released West Virginia's football schedule on Sept. 7.

This was the original 1918 Mountaineer football slate:

Oct. 5, Marietta

Oct. 12, at Pitt

Oct. 19, at Army

Oct, 26, Nebraska

Nov. 2, Michigan State (Charleston, W.Va.)

Nov. 16, at Rutgers

Nov. 23, Westminster

Nov. 28, Washington & Jefferson (Fairmont, W.Va.)

With H.P. Mullenex agreeing to assist McIntire on a temporary basis until the end of the war, West Virginia began practicing on Sept. 16 with a football squad consisting of 45 players. The vast majority of those guys were also part of the Student Army Training Corps (SATC), which was coordinated by the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) and was established through the National Defense Act of 1916 to help supplement the Army's shortage of officer candidates for the war effort.

The SATC was regulated by the U.S. War Department and participants were issued strict time parameters for specific areas of study. What it amounted to was a short window of less than three hours of free time for practice each day, with Saturdays open for games as long as players were back on campus by Sunday.

This proved a major obstacle for many teams, such as Pitt, which didn't have an on-site practice facility and used up a good portion of its time traveling to and from practice. Still, the Panthers were able to cobble together a five-game schedule in 1918 that included a 32-0 victory over Georgia Tech to earn it recognition as college football's national champion.

West Virginia's SATC players, for some reason, encountered much tighter time restrictions than their counterparts at Pitt, Penn State and other local schools, but McIntire forged ahead with preparations for the season nevertheless.

During one September scrimmage, the varsity team, led by halfback Jack Latterner, scored six touchdowns against the reserves and among the young players to emerge from that scrimmage were Martin, Kiger and Fuccy.

Those three were expected to be in West Virginia's starting lineup when the season opened on Saturday, Oct. 5 against Marietta.

Then, Philadelphia decided to have its Liberty Loan Parade on Sept. 28 despite a flu virus that was already overrunning the Philadelphia Navy Yard. More than 200,000 people attended that parade and soon the city became besieged with severe cases of the flu that ultimately resulted in more than 12,000 deaths in a six-week span.

The virus became known as the "Spanish Flu" because neutral Spain was the only country in the world to publicize its ravishing effects consuming the globe by the fall of 1918. Others, including the U.S., downplayed it because they didn't want to incite panic during wartime.

The virus had first shown up in the spring but died off during the summer before a more virulent mutation of it re-formed in the fall with far greater voracity. Cities such as St. Louis and San Francisco, which imposed draconian measures to limit social contact, were spared much of the carnage, while other cities such as Philadelphia and New York were not.

The virus had first shown up in the spring but died off during the summer before a more virulent mutation of it re-formed in the fall with far greater voracity. Cities such as St. Louis and San Francisco, which imposed draconian measures to limit social contact, were spared much of the carnage, while other cities such as Philadelphia and New York were not.At any rate, the virus made its way to Morgantown in late September and caused the cancellation of the Marietta game. Especially hard hit was the SATC, requiring the immediate quarantine of West Virginia's 45-member football squad. It was hoped that the quarantine would be effective enough to save the Pitt game on Oct. 12, but it was cancelled the week of the contest and West Virginia's Committee on Education abruptly ordered students to leave campus and not return until the virus was contained.

While away from campus, promising tackle Joseph Fuccy developed a slight cold that he didn't take too seriously upon returning to Weston, according to an account published in the Oct. 20, 1918 edition of The Pittsburgh Press. Fuccy's influenza soon developed into pneumonia and he died quickly. This second wave of the virus turned out to be particularly lethal to 20- to 40-year-olds - normally an age group that fared much better against the flu.

Fuccy's sudden death cast a pall on the football season, but it didn't totally eliminate efforts to reconstitute a team when students returned to campus on Nov. 5.

In the meantime, the city of Morgantown ordered the closing of all theaters, churches and other public places of gathering when it had reached more than 200 flu cases by November, according to Doherty Jr. and Summers.

The football games scheduled in October against Army and Nebraska, as well as the early-November meeting with Michigan State in Charleston, were abandoned, but Stansbury hoped to play the final contests against Rutgers, Westminster and Washington & Jefferson.

The W&J game was particularly important to Stansbury because the Presidents regularly drew crowds of more than 10,000, and the game was extremely profitable to the University and local merchants.

Then came the announcement on Nov. 9, two days before Armistice Day, that West Virginia was officially canceling its football season. The reason given was not the crippling influenza outbreak, which ultimately claimed the lives of more than 650,000 U.S. citizens, but rather the enormous time constraints imposed on the players by the SATC.

The regular rhythms of campus life soon returned to Morgantown, and the WVU basketball team completed a full 17-game schedule in the winter of 1919, although it probably should have reconsidered since it won just four of those contests.

The WVU baseball team, under second-year coach Kemper Shelton, won 14 of its 18 games later that spring, and a reconstituted WVU football team, with all of its star players from the 1917 squad back in the fold, had an outstanding season in 1919 with an 8-2 record that included a big victory at Princeton.

Ira Rodgers became the school's first consensus All-American football player in 1919 and helped put WVU on a path toward the most successful period of football in school history when Dartmouth's Clarence Spears took over in 1921.

Ira Rodgers became the school's first consensus All-American football player in 1919 and helped put WVU on a path toward the most successful period of football in school history when Dartmouth's Clarence Spears took over in 1921.The Football Review in 1944 listed West Virginia's grid teams of 1922, 1923, 1924 and 1925 among the nation's 10-best in the country – a consistent run of success approached only once since when Rich Rodriguez guided three Top 10 teams in 2005, 2006 and 2007.

Also, rising out of the ashes of that aborted 1918 football campaign was the construction of old Mountaineer Field, which officially opened in 1925 and served as the home for West Virginia University football until 1979.

Not even the most optimistic person living in Morgantown back in 1918 could have envisioned that ever happening when world war and a crippling influenza outbreak had grounded everyday life to a complete halt.

The lesson learned from what happened in 1918 applies to today's lethal strain of the COVID-19 virus that is systematically making its way across the country - limit your social contact to let this thing run its course!

Rich Rodriguez | Dec. 3

Wednesday, December 03

Reid Carrico | Nov. 29

Saturday, November 29

Jeff Weimer | Nov. 29

Saturday, November 29

Rich Rodriguez | Nov. 29

Saturday, November 29