Trailblazing Women in WVU Sports Tell Their Stories

February 28, 2021 10:00 AM | Women's Basketball, Track & Field, Blog

MORGANTOWN, W.Va. – Nineteen seventy-two was really the year women’s sports were born in the United States.

Of course, women were competing in sporting events in many parts of the country before that, and some were even willing to test the boundaries of men’s sports such as our Marilee Hohmann, who competed on the WVU rifle team in 1962, and Bette Hushla and Valerie Lewis, members of the men’s swimming team in the mid-1960s.

But it was in 1972 when an idea became a law.

That’s when the Federal Government introduced Title IX, which stated “no person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subject to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal assistance.”

For West Virginia University, mountains needed to be moved – and quickly!

“They saw the handwriting on the wall,” WVU women’s sports advocate and pioneer Kittie Blakemore recalled in 2013. “You have a big land-grant institution that is going to lose a lot of federal money if they don’t go with this.”

According to Blakemore, what kept WVU from introducing women’s sports immediately was the fact that the state didn’t know how it was going to pay the new coaches. When it became evident that the coaches were also teachers being compensated through the School of Physical Education, that issue became moot.

So, women’s basketball, gymnastics and tennis made their West Virginia University debuts during the 1973-74 academic year.

Volleyball and swimming were added the following year, with softball (1975-76) and track and field and cross country (1977-78) introduced in subsequent years.

“The athletic department really didn’t want us, but they knew – and I think (director of athletics) Leland Byrd knew – they were going to have to do this,” the late Blakemore recalled.

Blakemore, who helped draft the original constitution for the West Virginia Intercollegiate Athletic Conference, steered the WVU women to the WVIAC for the first few years of existence until the sports teams could get established. The women’s rosters during those first few years basically reflected this; they were filled with mostly club, recreational and walk-on players seeking to maximize their collegiate experiences.

Toward the late 1970s, however, when the Mountaineer women were forced to play stronger schedules, there was a greater need to recruit more talented and more skilled players to remain competitive.

That meant pursuing student-athletes of all races. It also meant providing more financial and scholarship support, which was severely lacking in those early years.

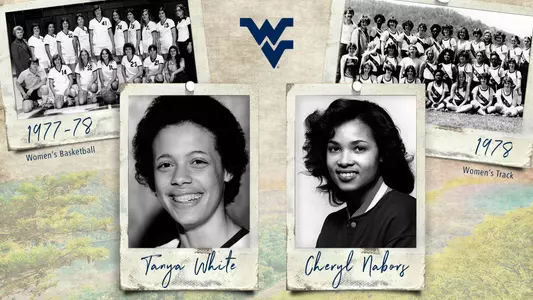

Four years after WVU women’s sports got off the ground, the first Black female athletes in school history began competing for the Mountaineers. Women’s track and field had five pioneering athletes: Cynthia Jeter, Judith Johnson, Lillian Miller, Cheryl Nabors and Jan Saunders.

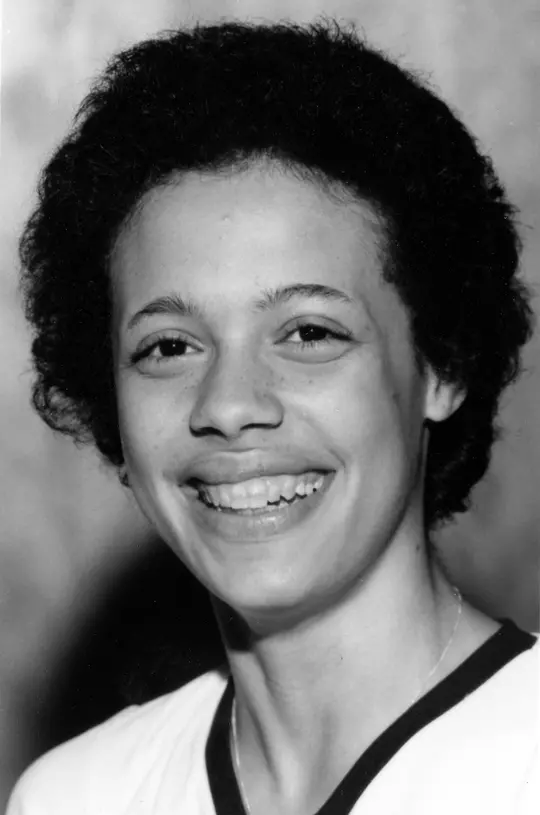

Charleston’s Tanya White blazed the trail in women’s basketball. These six are West Virginia University’s pioneering Black female athletes.

Their individual stories are like those old Russian nesting dolls; each one you open reveals another doll, or another story - some uplifting and inspiring and, yes, some sad and unfulfilling.

Nabors, a self-proclaimed Army brat from Institute, West Virginia, wasn’t even aware that she was clearing a path for others when she became a member of West Virginia University’s first women’s track and field team in 1978.

She simply just wanted an opportunity to continue competing in athletics after high school.

Like it did for many young women of that era, Title IX enabled Cheryl to participate in organized sports for the first time in the mid-1970s. Her freshman year in high school she remembered having to use a softball instead of a shot put, and the opportunity to do something like that in college seemed totally foreign to her at the time.

Then, after she enrolled at WVU as a National Honor Society student, she found out about a women’s track club the school was sponsoring during her sophomore year in 1976. It was an opportunity, albeit one under Spartan conditions.

“We were just trying to get recognized as a varsity sport, so we did fundraisers and had to come up with our own modes of transportation,” Nabors, now Cheryl Phillips, recalled. “We went to one track meet down in Huntington and used a U-Haul truck as transportation for the team.”

Yes, the club team actually rode in the storage area of the U-Haul to its track meet!

Their uniforms consisted of one blue t-shirt with the words “Support Women’s Track” emblazoned across the front. What mattered most to Cheryl and her teammates when they became an official University-sponsored team in 1978 was they were finally getting uniforms! And, more importantly, they also had a real coach – Linda King.

“I wasn’t even thinking about this from an integration perspective,” Phillips admitted. “This was a sport I loved, and I could continue doing it. Uniforms? What a novel concept. I even got a varsity jacket, and I still have it!

“I give credit to those who paved the path for us,” she continued, pointing to the male athletes who came before her in the 1960s and early 1970s, as well as Horace Belmear, who was responsible for recruiting and retaining Black students at WVU in the 1970s and 1980s. Horace and his wife, Geraldine, became the surrogate parents to many, many Black WVU students and athletes during that era.

“I never experienced the discrimination that a lot of people did,” Cheryl admitted. “Even when I was here there were others who said they had experienced some of those things, but, personally, I did not. I was an Army brat, and my father raised me to believe the only difference between us and a Caucasian person was the amount of pigment in our skin. We all have red blood.”

Cheryl enjoyed a successful two seasons competing on the women’s track team, even setting a school record in the shot put that lasted a couple of years after she graduated. Her experience at WVU was so fulfilling that she chose to remain in Morgantown, became an employee at WVU and raised her family here. She currently works in the Division of Talent and Culture as a Human Resources Information Specialist (Sr).

Her son Bryan, a Queens University graduate, now works in the Mountaineer Ticket Office and her daughter, Tiana, is a WVU graduate working at the Evansdale Library.

“I grew up believing you can do anything you put your mind to,” she said of her experiences coming of age as a young woman in the 1970s.

Tanya White-Woods felt the same way growing up 10 miles down the road from Cheryl in Charleston. When she was a little girl, she loved basketball so much that she would pedal her bicycle all over the city looking for pickup games, sometimes going from Kanawha City all the way over to Dunbar.

Back then, there were no pick-up games for girls to play so she had to take matters into her own hands. If the guys wouldn’t choose her to play she would just hang around until a game was over and call “next!”

That meant she got to pick her own team to play.

“A lot of the guys remember me as being that pesky girl that kept showing up at their games,” White-Woods laughed.

These weren’t just your run-of-the-mill park players, either. She was on the court with some of Charleston’s best in the 1970s, guys who played college basketball such as West Virginia’s Curt Price, Deacon Harris and Levi Phillips, Cincinnati’s Mike “Twig” Jones and Curtis Cabell and Louisville’s Sam Brooks.

There was John Britton, a sixth man on Lou Romano’s 1974 Charleston High state championship team who went to Akron and broke a bunch of records there.

There was Charles “Dickie” Russell, who later played for Price at West Virginia State. Lowell Harris was a good playground player who ended up at King College. Dennis Harris played at Morris Harvey.

Playground legend Ameche (Meechie) Watson earned local fame for causing Charleston High’s undefeated team in 1973 to have all of its wins temporarily wiped out by the SSAC right before the state high school tournament because people felt he lived in a part of the city that required him to attend rival school Stonewall Jackson instead.

The SSAC eventually reversed its decision and permitted Watson to play in the state tournament, and the Mountain Lions won another state title, so recalls my good buddy and Charleston sports authority Frank Giardina.

Tanya White didn’t play with all of these guys, but those were the types of players in the pick-up games she was crashing. Phillips, one of only four players in WVU history to record a triple-double in a men’s basketball game, remembers Tanya well.

“She could play,” he said. “She was the type of player who dove on the ground for loose balls or didn’t mind getting knocked down by guys much bigger than her. She held her own playing against us - and she dominated the women.”

In the meantime, Blakemore’s West Virginia basketball team was beginning to wear out its welcome in the WVIAC. Her squad finished fourth in the state tournament its first year in 1974, improved to second in 1976 and finally won it in 1977.

They were in the process of transitioning fully to the AIAW, which oversaw women’s sports before it made the move to the NCAA in 1982. Many of the teams West Virginia began playing in the late 1970s were much stronger, more athletic, more skilled and more seasoned than what they had faced in the WVIAC.

That meant Kittie needed more of those types of players in order to remain competitive.

Tanya played basketball at Charleston High, but girls games in West Virginia took place in the fall to avoid scheduling conflicts with the boys, which meant that their exposure to college teams was severely limited. She said her high school coach was also the school’s vice principal and had never coached the sport before. He would watch Boston Celtics games on the weekends and then try to incorporate some of what he learned into those Charleston High girls games on Thursday nights.

“We had a decent team,” White-Woods said. “We didn’t win the championship, but we were pretty good considering. Cathy Meadows played on the WVU team for a couple of years, and she came through Charleston High as well.”

According to Tanya, Kittie never saw her play in person. She relied on a recommendation from her close friend Helen Haworth, the preeminent female sports authority in the Kanawha Valley at the time. Helen was a gym teacher and a coach, and Kittie recruited Tanya based solely on Helen’s word.

In the mid-1970s, WVU women’s teams were only awarding a couple of scholarships per year, so earning one was a pretty big deal. In addition to receiving an athletic grant, Tanya also qualified for a Board of Regents scholarship, which meant Kittie could work the system a little bit. If Tanya was willing to forfeit her athletic scholarship and accept the Board of Regents grant, that meant Kittie could put another deserving player on scholarship – basically a three-for-two deal.

Tanya said she agreed to do it.

When White-Woods began playing with the other team members, it was clear right away there were significant stylistic differences. Tanya grew up playing a certain style of basketball in Charleston against bigger, stronger male players that really didn’t suit the way Kittie’s teams were playing at the time.

“I was the fastest player on the team, so I would take off for fast breaks and Kittie would yell at me and say, ‘Don’t run so fast!’” White-Woods recalled.

She appeared in 20 games her freshman season, was one of the top players coming off the bench as a first-year player and provided a spark in several of the games the Mountaineers won that season. WVU had an 18-9 record, beating Villanova and Virginia Tech outside of conference play, finished second to Marshall in the state tournament and lost by 23 to Ohio State in the AIAW Midwest Regional in Columbus.

It was Kittie’s second-best team of that period and her best until 1985 when a fully integrated team that included Olivia Bradley, Kim Brown, and Georgeann and Marva Wells won 20 games and earned a bid to play in the Women’s Invitational Tournament.

Following her freshman season, Tanya did not make the squad in 1978-79.

“I was the first Black,” White-Woods said. “It was a difficult time and a very difficult path for me and my teammates to understand at that time. Kittie had had the basketball team for four years, I believe, and they had basically the same group of girls there. My year was the first year they really had new blood coming into the program.”

White-Woods admits there was some gossiping going on within the team that sort of took on a life of its own. She believes that played a role in her being cut from the squad when she was asked to try out again for the team right before the season started in October.

White-Woods said she was later asked if she would like to continue her basketball career at WVU, but she felt things had become too awkward for her to continue.

Keep in mind, there was no support system in place here or anywhere else to address these types of issues back then. There were no sports psychologists, no student-athlete enhancement coordinators nor diversity training programs in place for players and coaches.

“There was no dealing with racial tensions on the team,” she admitted. “It was just something that I wasn’t to discuss. The few times that I tried to discuss these things I was shut down.”

The athletic department then consisted of about 25 or 30 employees made up mostly of middle-aged white men. Where was Tanya to go for advice and counseling?

In whom could she feel totally comfortable confiding?

And, where could Kittie go to help her better understand the generational and cultural differences now coming into play on her teams? She didn’t have a budget to hire a full staff and instead had to rely on young and inexperienced graduate and student assistant coaches.

They came and went on a yearly basis and in some instances, were using their positions on the basketball staff to get their master’s degree to pursue other vocations. Some of the student assistants working in department at the time were simply not equipped to handle the responsibility of working on a personal basis with 18-, 19-, 20- and 21-year-old college players.

“It was a mixed bag for me, and it was really part of the growth and evolvement of society at that time,” Tanya admitted. “It was part of what happened to a lot of Black athletes back then.”

After her one season playing at WVU, she remained in school for another couple of years until she married her now ex-husband and moved with him to Canada where he played professional football.

Tanya returned to Morgantown to continue her education during the spring semesters before eventually moving to Hamilton, Ontario, year-round. She enrolled at McMaster University and was going to continue her basketball career there until she got pregnant with her son, Julian.

Julian, by the way, came to WVU and earned a law degree. He is currently working as human resource director at the West Virginia Department of Transportation.

Tanya has also enjoyed a successful professional career. In the early 1990s, West Virginia governor Gaston Caperton appointed her the state’s equal employment opportunity director and in that role she implemented some of the EEO and diversity training programs still in place today.

She’s done HR consulting work for many companies in the state, and presently serves as HR director for Better Foods, which manages Gino’s Pizza and Tudor’s Biscuit World restaurants in four different states, while also continuing her White-Woods Consulting business.

But she could never quite give up basketball.

For many years after leaving WVU, she continued to play in AAU and rec leagues, oftentimes driving to Richmond to play games on the weekends before returning to Charleston for work on Monday mornings.

She kept a pair of high-top sneakers in her car and would often change from a business suit into her basketball clothes to play evening pickup games at the local gym.

There were also flirtations with a number of women’s professional leagues that never quite got off the ground. She remembers once going through preseason practices and then right before the start of the season being locked out of the gym before the first game. Now 61, White-Woods said she played and coached Senior Olympics basketball until a few years ago when her knees became too bad to continue.

Other than following her niece Talisha Hargis’ outstanding WVU career in the mid-1990s, Tanya’s involvement with Mountaineer sports consisted mostly of watching football and men’s basketball games on TV.

But her love and devotion to West Virginia University never wavered.

“It’s still my school,” she says. “I have friends in Canada that I’ve sent West Virginia gear to wear when they watch football games. It’s the family school. My brother Adrian attended WVU. My son, Talisha and her brother William also attended WVU. It just didn’t work out for me.”

College basketball may not have worked out for Tanya, but her brief time playing for the Mountaineers did help many others who came after her. And, Kittie unquestionably learned a great deal from her one-year experience with Tanya. Uniontown’s Laurie Evans followed White-Woods on the WVU team in 1978, and Tonya was around to help Laurie deal with some of the same issues she experienced on the team.

Junior college star Janice (J.D.) Drummonds and Frederick, Maryland, prep sensation Cathy Parson arrived in 1980 and enjoyed hall of fame careers at West Virginia. Bradley, from Bradenton, Florida, was a wonderful player for the Mountaineers in the early 1980s and became a WVU Sports Hall of Fame member, as is Georgeann Wells, who earned national fame for becoming the first woman to ever dunk a basketball in a college game. Three decades later, four-year WNBA performer Bria Holmes is probably the most talented performer to ever put on at Mountaineer uniform.

Their West Virginia University lineage begins with Tanya White-Woods in 1978.

Tanya understands completely that her experience as a college basketball player in the late 1970s was part of a passing of the culture, as you often hear today. But insensitivity matters. Words not chosen carefully can be wounding, sometimes permanently. Something uttered 40-some years ago in passing may have been long-since forgotten, but not necessarily by its recipient.

Those are some of the lessons Tanya teaches today working as an EEO and HR specialist.

“It was changing, but it didn’t really change until WVU got multiple African-American players on the team at one time,” she said. “I get it.”

Which begs the question: Would she have rather come of age 40 years later, with so many more opportunities for women in sports today?

“I lived my life without regret, so I can’t say that’s true because it was necessary for me to come when I did, and it was necessary for me to experience what I experienced,” White-Woods said. “But I do see the growth and opportunity that’s out there for girls today.”

Tanya said she once sat down with Kittie years ago, and they had a good cry together. Both likely came to an understanding that their paths had crossed at a time when neither fully understood the other’s point of view – to no fault of their own.

“I was there when I was 17,” she said, unsuccessfully suppressing her tears. “I was young and dumb and didn’t know much, and it’s been a long time. It’s almost 50 years now, so I finally get to tell my story.”

Today, collegiate athletics has become as diverse as our country, and our women’s sports teams at West Virginia University certainly reflect that. Shirley Robinson opened the door to women’s tennis players in 1981 and today serves on our WVU Sports Hall of Fame committee.

She works on WVU’s Advisory Council of Classified Employees.

Verneze Moore integrated women’s cross country in 1982, Yvette Clark-Spratling was the first to compete in women’s gymnastics in 1987 and the Patterson twins, Valerie and Vanessa, cleared the way for others in women’s swimming and diving in 1992.

Stacey Adams was a member of West Virginia University’s first women’s soccer team in 1996 and Nikki Hardy arrived in 1997 to play for volleyball.

And, most recently, Joanna Thompson became a member of the rowing team in 2007, not too long after rowing became an athletic-department sponsored sport at WVU.

Just like those old nesting dolls … when opened, each has her own personal story to tell.

This is our second in a series of stories celebrating Black History Month at West Virginia University.

Other WVU Women's Trailblazers