Remembering West Virginia University’s Pioneering Student-Athletes

February 09, 2021 04:05 PM | Football, General, Blog

MORGANTOWN, W.Va. – Tangela Cheatham, our talented student-athlete enhancement director, popped her head into my office one Monday morning.

This particular Monday morning also happened to be Dr. Martin Luther King Day, which made me embarrassed to be seen working on a national holiday that recognizes the amazing accomplishments of a great humanitarian.

My door was only cracked slightly, and the jazz on my Spotify playlist was turned down lower than usual because I just wanted to get a few things done discreetly before taking the rest of the afternoon off.

Tangela was dressed just as I was, in sweats and a sweatshirt, and I’m sure she was taking care of a few odds and ends of her own. In the sports profession, the odds and ends never seem to end – no matter what time of year it is!

She mentioned to me that Black History Month was coming up in February and wondered if I would write something to give our student-athletes and fans a historical perspective on West Virginia University’s pioneering athletes of the 1960s and 1970s.

“You’re the history guy here,” she said, smiling.

I told her I would.

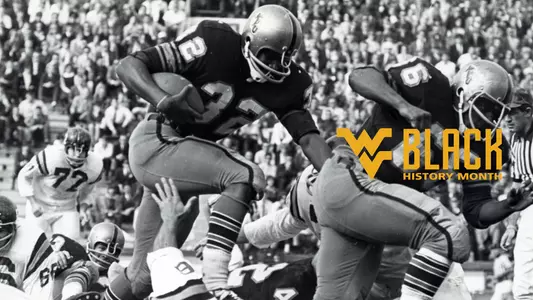

As some of you are probably aware, I’ve written pieces in the past about West Virginia’s pioneering football players Dick Leftridge and Roger Alford, who integrated Southern Conference football in 1963. I also wrote about the great Ron “Fritz” Williams when he died suddenly of a heart attack in 2004.

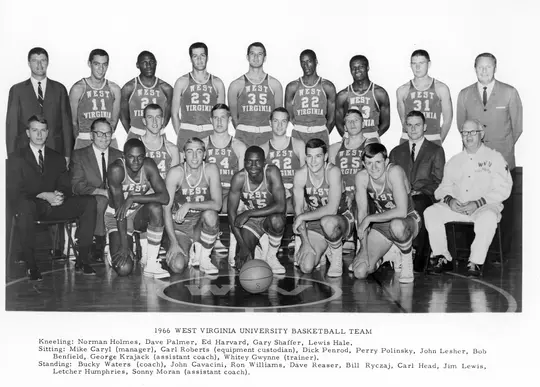

His teammate Jimmy Lewis called the office to inform us of his death and was passed along to me. I spent the next hour and a half completely mesmerized by his stories about Fritz, himself, Norman Holmes and Ed Harvard – WVU’s men’s basketball pioneers.

Instead of talking about what a great player Fritz was, Jimmy discussed their experiences being young Black men coming of age in the mid-1960s in a predominantly white college town.

He explained to me that the experiences he was used to growing up in Northern Virginia simply weren’t available here in Morgantown. He had to get his hair cuts in Osage. Fraternities were a vital part of the collegiate social experience in the 1960s and for him to join a fraternity, he had to do so at Pitt, of all places.

Rhythm and blues, soul and jazz music were rarely played on the local radio stations and interracial dating in the 1960s was considered a tremendous risk. A football player once told me that an unnamed assistant football coach told him that interracial cohabitating was illegal, and if any player was caught doing it, he would have to find another place to play.

What else was the player supposed to do, considering there were only a handful of Black girls on campus at the time?

That’s just a small sampling of what our pioneering athletes had to endure in the 1960s – not just in Morgantown, West Virginia, but in Blacksburg, Virginia, College Park, Maryland, State College, Pennsylvania, Columbus, Ohio, Lexington, Kentucky, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and many, many other places around the country as well.

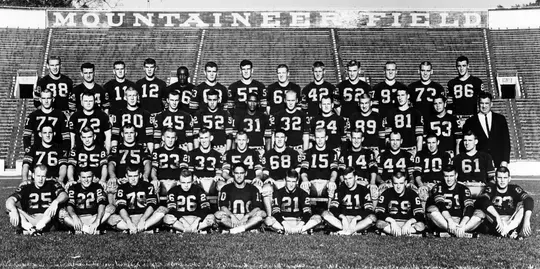

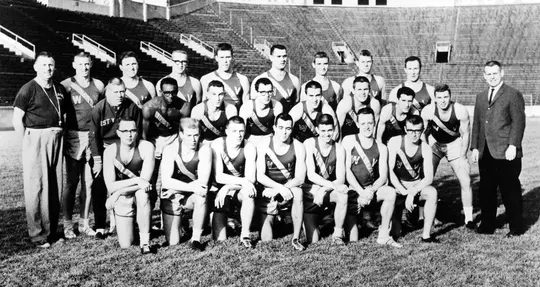

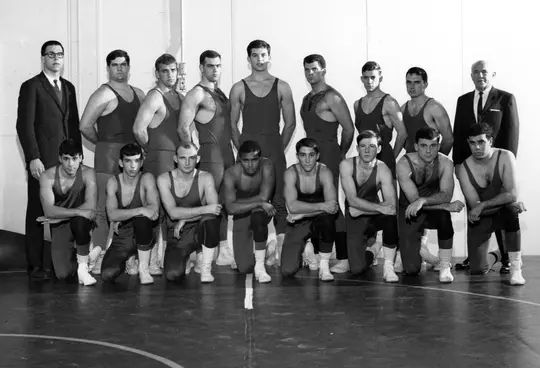

Look at all of the pictures of the West Virginia University’s teams that were integrating in the 1960s – men’s track in 1962, football and men’s soccer in 1963 or wrestling in 1967: one or two Black players surrounded by a sea of white faces.

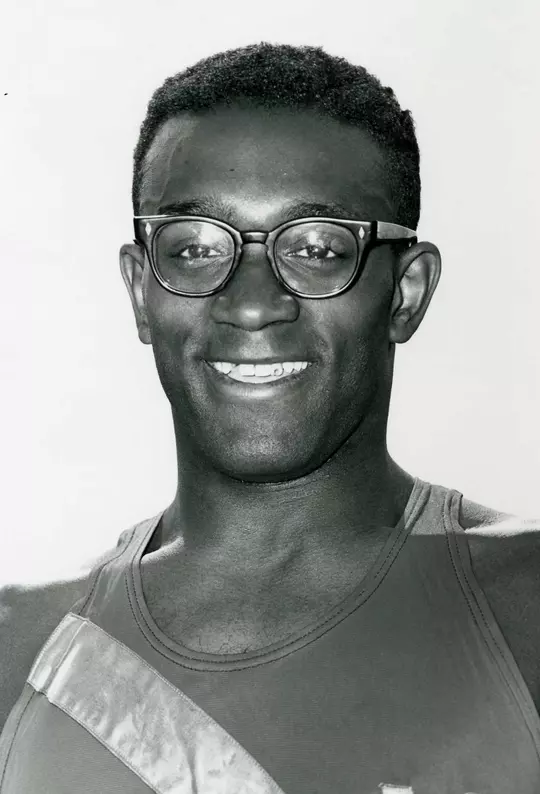

Morgantown jumper Phil Edwards was the first to integrate WVU sports in 1962, to be followed by football players Leftridge and Alford in the fall of 1962 as members of the freshman football team. Tanzanians Peter Mpanga and Stan Mhina arrived in the fall of 1963 to play soccer and then Lewis, Williams, Holmes and Harvard integrated Southern Conference basketball in 1964.

Recently deceased Maurice Moon, from nearby Connellsville, Pennsylvania, was a record-setting jumper and sprinter for the Mountaineers in the mid-1960s.

Football’s Norman Holmes was considered WVU’s first Black wrestler in 1965, but Morgantown’s Jimmy Stevens was the first recruited specifically to compete in the sport for the Mountaineers in 1967. He was the Southern Conference 137-pound champion that year.

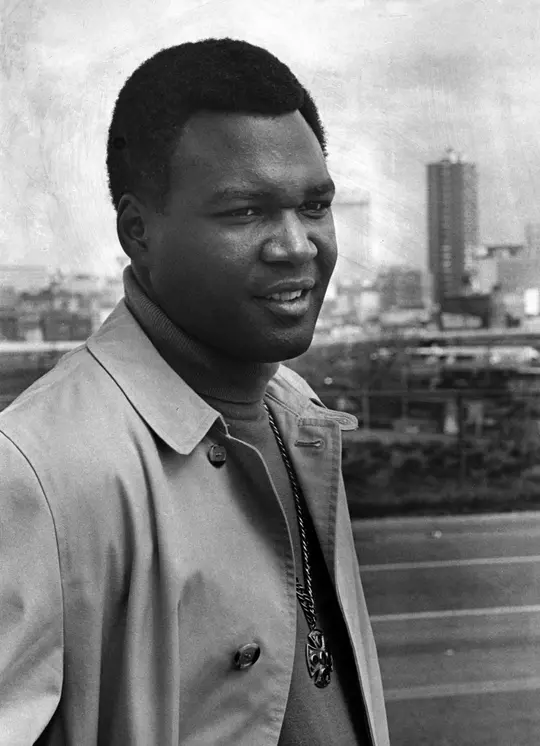

The second wave of Black football players at WVU in the mid-1960s included Garrett Ford Sr., who became the first Black assistant coach in any sport at West Virginia in 1970. Ford later was also the first Black senior administrator during a wonderful 44-year athletic career at WVU that concluded with his retirement in 2011.

I got to know Garrett well during the early 2000s, and one afternoon he stopped by my office to unburden himself, I suppose. His college teammate Dick Leftridge had just died, and I think he wanted to tell someone Dick’s story, and he knew I was a pretty good listener.

He also knew I owned a recorder and had a propensity for keeping anything historical.

I came to learn that Garrett’s story growing up in Washington, D.C., was similar to Dick’s living in Hinton, West Virginia, in the late 1950s.

“I grew up in predominantly a Black area,” Garrett began. “There were very few whites around. The only white guy in our neighborhood was an insurance guy who came by occasionally to get insurance money from my mother.”

Just like Leftridge, Ford became one of the top running backs in the country while starring at all-white DeMatha High, where coach Morgan Wooten arranged to have Garrett picked up from downtown every morning and driven out to Hyattsville, Maryland, to go to school.

He’d stand on a street corner wearing his navy blue DeMatha blazer waiting to be picked up. It was about a 25-minute drive one way.

“There were 250 boys in the school and only five of them were Black,” Garrett remembered.

DeMatha was better known for its basketball, but it did give Ford the exposure he needed to get many scholarship offers, including one from his dream school, Syracuse.

“Jim Brown was my idol growing up, and I wanted to wear No. 44, just like him and Ernie Davis,” Ford said. “I remember when I made All-Met, which is the equivalent of making all-state, I met the Syracuse coaches, and they promised me I could wear 44.”

Then one day, Ford got a phone call out of the blue from a guy named Bob Guenther from Gaithersburg, Maryland. Guenther once played football at WVU and was doing some bird-dogging on the side for football coach Gene Corum, who had signed Leftridge and Alford to scholarships at WVU two years prior.

Guenther told Garrett West Virginia was really interested in him, had already integrated its football program and could arrange a meeting with Corum and assistant coach Dick Ware at his high school.

Ford, knowing very little about WVU, wasn’t all that interested. All he really knew about West Virginia was it was Jerry West’s school and was better known for its basketball at the time.

But Guenther was persistent, and Ford said he would come on a visit if he could bring all of his buddies with him. Six of them, including Ford, piled into Guenther’s car for the daylong drive on those twisting, two-lane Maryland roads feeding into West Virginia.

“It took forever to get there and when we finally got to the old iron bridge at Cheat Lake that about did it for me,” Garrett laughed. “We came down through Bruceton Mills and all those little towns. Here is this bridge that looked just like an erector set. I always thought that thing was going to fall down.

“So we cross that bridge, went up over the hill and finally got down into Morgantown,” he said.

After visiting the downtown campus – that’s basically all there was in the 1960s – Garrett and his buddies were introduced to Dick and Roger. They showed them the parts of town the white football coaches didn’t.

“Roger was from Wintersville, Ohio, and Dick was from West Virginia,” Garrett said. “Dick might have been the best football player I ever saw, and Roger was a serious student. Roger wound up getting like four degrees from here and later became a successful dentist in Detroit.

“So, they took us to Osage. They took us to Pursglove. They took us to White Avenue where the Black people in Morgantown lived. I saw very few Blacks when I was there.”

They met Chuck Blue’s family. Chuck's older brother, Kenny, was a tremendous basketball player at Morgantown High in the mid-1950s and later became an esteemed professor at Marshall University. The Blues were well-respected and highly regarded in Morgantown, according to Jay Jacobs.

It was Chuck who took Garrett and his crew down to a little place on Clay Street.

“It was a small place where the Black people went,” Ford said. “It was full of coal miners and here I am, 18 years old from Washington, D.C., and I’m being indoctrinated to this culture. I had never seen anything like this before in my life!”

What young Garrett Ford saw for the first time were poor white people intermingling with Blacks. To say he was astonished was an understatement.

“The thing about Black people and white people in West Virginia was they were poor together,” he said. “I remembered going in places in West Virginia where it didn’t matter if you were Black or white – everyone had the same set of circumstances. The Black people here had like a brotherhood with their white friends. There was no difference.”

Morgantown was also the first time he had ever seen white garbage collectors. All of them were Black where he grew up in D.C.

One of Ford’s classmates at DeMatha was the son of the No. 2 person at the U.S. Treasury Department, and he remembers him once showing up to school in a brand, new red convertible he had gotten for his birthday.

Ford said the privilege was off-putting.

“Then here I am in Osage, which wasn’t very nice, but the people there were very nice to us,” he said. “The thing that sold me on West Virginia was the people I met. You’d meet people here and they’d say ‘thank you’ and ‘come again.’ You’d hear, ‘How are you doing?’ on the street. And people here meant it when they asked you that. You didn’t hear that in the city.”

Ford’s second visit to Morgantown resulted in him signing to play for the Mountaineers.

“(Childhood sweetheart and wife Thelma’s) family was really proud that I was going to West Virginia,” he said. “They knew more about the advantages of getting a scholarship than I did. It was a heck of a time in American history because integration was just happening everywhere.”

Ford admitted it wasn’t always easy being a young Black man in Morgantown in the mid-1960s. He had to deal with unintentional slights on a daily basis.

“There were some rough times, no question. There was a guy recruited on the basketball team from D.C. named Carl Head, and we hung out a lot together,” Ford said. “Kids would speak to you in class, but once they got outside they didn’t speak to you anymore.

“But I don’t blame the kids because that’s just the way things were – that’s how people grew up,” he continued. “It was hard on us, and we all ended up bonding together – Jim Lewis, Carl, Fritz Williams and the basketball guys. I had no idea what a big deal Fritz Williams was; he was a heck of an athlete.”

One hot spring afternoon, Ford, classmate John Mallory and Leftridge were in a downtown department store shopping for sodas. All eyes were on them from the moment they walked into the place until they left.

When they were outside again Mallory, from Northern New Jersey, said, “Man, did you see that? The people here really make a big deal out of the football players, don’t they?”

Leftridge replied, “No man, they were staring at you because you’re Black!”

“We played a lot of basketball together; that’s what we did,” Ford said. “That’s really all we did. The sad thing is they wanted us here as athletes, but they did not know what to do with us once we got here. There were no social activities for us. There were no barber shops for Blacks. My wife had to go to Fairmont to get her hair done. The music was never geared toward the Black kids.

“But I chose to be here.”

Ford was not prepared for what he encountered playing football games on the road at some of the southernmost schools in the Southern Conference either – the confederate flags and the bands playing “Dixie.”

At one place, he was told to be in his hotel room before dark because his safety wasn’t guaranteed. Then, when the new coaching staff replaced Corum in 1966 – all Southern white men who had never coached a Black player before – Ford grew extremely suspicious.

He was most suspicious of assistant coach Bobby Bowden because Bowden was from the worst city in the U.S. for race relations at the time – Birmingham, Alabama. He had even heard that Bowden’s mother was a George Wallace supporter.

“When Coach Bowden got here he’d come up to you and innocently say, ‘How you doin’ boy?’ He had a thick Southern accent during a time when Black Power was becoming popular, and he’d always say ‘boy’ but he meant nothing by it,” Ford recalled.

“My attitude was like, ‘You’re a white man from the south and you don’t know me!’ That was the way I was coming at him,” Ford said. “Well, he invited me over to his house one evening for dinner. I had never been in a white person’s house for dinner and here was this man from Alabama and he invites me to his house to eat with his family.”

Ford did not want to go, but he felt he had no other choice because Bowden was the team’s offensive coordinator.

“I went to the house and eventually I’m bouncing Terry and Tommy off my knees; they were just little kids then. It was the nicest family you’d ever want to meet,” Garrett said.

In 1970, a couple of years after an ankle injury prematurely ended Ford’s professional football career with the Denver Broncos, he got a job working in the banking industry in Boston.

Ford had heard his old offensive coordinator had gotten the West Virginia coaching job, and he sent him a note of congratulations. Soon afterward, Bowden called him and offered him a position on his coaching staff. Garrett remained at West Virginia University for the next 41 years.

“My wife went to school here, my two children were raised here and went to school here,” Ford said. “It’s the best decision I ever made.”

Even in 2006, Garrett, then approaching retirement age, just couldn’t bring himself to leave Morgantown to enjoy the warmth and sunshine of Florida. He loved the excitement and enthusiasm when the students – of all races – returned to campus each fall for another semester.

“I would use the same set of jokes and stories each year and my son (Garrett Jr.) would say, ‘Dad, you’ve used that same speech for years!’ My speech never changes,” he chuckled.

At this point, I could sense Garrett was pleased that he was able tell someone else his story about living in Morgantown in the 1960s. He then reflected on a wonderful career spent at West Virginia University, first as one of its pioneering athletes and then as a pioneering administrator.

“I wanted to have an impact on the lives of kids,” he said. “I think I’ve done a good job of that. It bothers me that I’m getting old now because I used to remember when I was younger and I used to watch (John) Seamon and all of those old guys walking around here. Now I’m the old guy!

“But I’m happy with the way things have turned out in my life,” he quickly added.

Today, 15 years after that random afternoon conversation about Dick Leftridge and their experiences as Black men coming of age in the 1960s, I think of Garrett’s grandson, Bryce Ford-Wheaton - Tracey’s son and Garrett Jr.’s nephew - today a member of Neal Brown’s West Virginia University football team.

History often has a way of coming full circle - or at least rhyming, as Mark Twain used to say.

Bryce is a now third-generation Mountaineer, thanks to his granddad and a whole bunch of other pioneering athletes in the 1960s and beyond!