Frazier’s Passion For Football Positions Him For Future Success

May 04, 2021 05:10 PM | Football, Blog

MORGANTOWN, W.Va. – Do you want to know the real reason why Fairmont’s Zach Frazier became a rare true freshman starter on West Virginia’s offensive line last season?

Well, size, ability and athleticism are obvious reasons, for sure. Offensive line depth, or lack thereof, was another.

But what really tipped the scale and convinced Neal Brown to play his precocious freshman is Frazier’s pure love of the game.

The dude eats, drinks and sleeps football.

This is a guy who’d just as soon sit at home on a Friday night watching old West Virginia games with his father, Ray, than go hang out with the fellas.

“He’s a little different now,” Matt Moore, West Virginia’s assistant head coach and offensive line coach, said recently. “That kid is a football guru. He loves it. He likes to dissect plays with his dad. That’s kind of always been their deal together. They don’t go golfing or fishing, they sit around and watch old games trying to figure out where the mike (linebacker) is, the three-technique and who needs to be double teamed.”

“Playing college football has always been my dream,” Frazier said a couple of weeks ago.

This trait is seemingly becoming more uncommon among players these days, but not to those who played center early in their careers, great Mountaineers such as Tyler Orlosky, Eric de Groh, Mike Compton, Kevin Koken and Bill Legg, among others.

Rimington Award winner Dan Mozes began his college career at guard before switching to center early into his junior season in 2005. His first-ever shotgun snap in a game against Maryland near his own goal line almost sailed over quarterback Pat White’s head out of the end zone.

As good as he was, Mozes learned right away that it’s a little bit different when you have the ball in your hand and there is a guy lined up right overtop of you.

As for de Groh, he was probably the most intelligent football player to ever suit up for the Mountaineers. I remember once being mesmerized listening to him on a plane ride coming home after a game and him talking about information storage and computer processing capabilities long before any of us had ever heard the words “cloud storage.” The guy is just Einstein-level smart.

Legg, who coached de Groh at WVU, said he had no hesitation whatsoever playing him at such a young age because he could process things so quickly.

“I would look at Eric and say, ‘Eric, do you remember last year when we were playing Virginia Tech and they played this front and we’re running this play and what the adjustment was?’ He’d go, ‘Yeah, this is the call’ and I’d go, ‘Yeah, well we’re going to do that this game, too’ and then I would go and coach the other guys,” Legg laughed.

Compton, today an offensive line coach at Division II UVA-Wise, was different than others simply because he was a freak of nature - a 6-foot-7, 290-pound mountain of muscle and athleticism who was physically ahead of everyone else his age. Compton was probably the most advanced offensive lineman to sign with West Virginia since Bruce Bosley in the early 1950s.

“How many guys are that size and that athletic coming out of high school?” Legg marveled of Compton. “You just don’t have that.”

By the way, I’m hearing similar things being tossed around about Spring Valley offensive lineman Wyatt Milum, who is set to arrive on campus sometime this summer.

Koken and Legg, however, were virtual clones - developmental guys who consumed football for breakfast, lunch and dinner. They thought about the game 24/7, much like Zach Frazier does today.

Koken, vice president for FedEx Ground who today lives in Cranberry Township, Pennsylvania, said one of the happiest moments in his life was when he became old enough for his father to finally allow him to play football.

“When I got to the point when I was allowed to play all those years ago, I can still remember exactly where it was and exactly what it felt like walking onto that field for the first time,” he said. “I walked through a path to this park and when I saw the field I said to myself, ‘This is what I want to do and this is where I want to be!’”

For Legg, now coaching Marshall’s tight ends, it was a similar deal when he starred at Poca High and later at WVU.

“I brought my lunch to the stadium and ate lunch while I watched film with coach (Mike) Jacobs, who coached me, coached Koken and coached Compton as well,” he recalled. “I asked him questions if I needed to know something or asked him what he was thinking so I could start processing it in my head. Then, I would go downstairs and get changed and come back up to sit through a meeting with the whole offensive line before going to practice.”

Koken played for an advanced high school program at Youngstown’s Cardinal Mooney, which had a reputation at the time for developing major college offensive linemen. His high school coach always put his most athletic offensive lineman at center and worked his players tirelessly on fundamentals and technique.

Koken also had an older brother who played college football, and he once gave him some great advice before he left for WVU in 1984.

“His key messages to me were to be in shape and always pay attention,” Koken explained. “When you are in shape, that’s the best way to pay attention because you are not sucking wind when the coaches are talking, so you are able to listen and learn.”

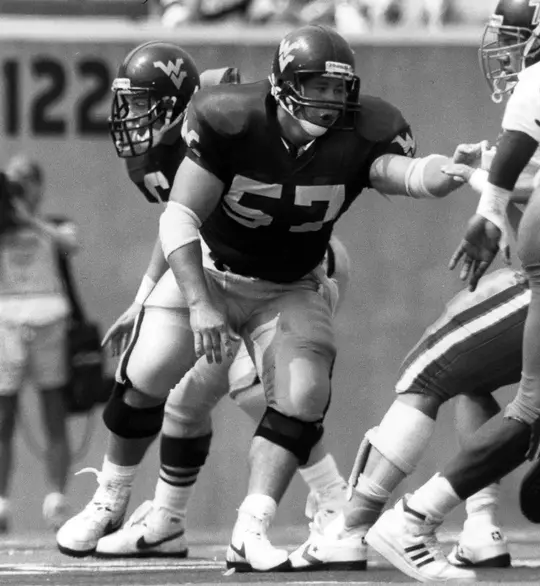

Koken wasn’t the strongest player on the football field, but he became a three-year starter for the Mountaineers and was a key member of a dominant offensive line that helped them reach the national championship game against Notre Dame in 1989. He developed into a tremendous center because he mastered the fundamentals of the position and was a devoted student of the game.

“Using the right technique can help you beat anyone,” he noted. “I wasn’t super-strong, so I focused a lot on technique, particularly early in my career. I didn’t weigh what Zach weighs now until I got to training camp in Philadelphia, so he’s got that going for him.”

Legg was even smaller than Koken when he became West Virginia’s starting center during his redshirt freshman season in 1981. Mentally, Legg was ready to play; physically, he wasn’t.

The very first play of his college career at Virginia, he failed to be assertive on his line call, and guard Andre Gist and tackle Mike Durrette both pulled on a trap play. After that, Gist threatened him if he didn’t tell them what to do after each play was brought into the huddle.

“Mike Durrette used to get mad at me because I was telling him what to do on every play and 99.9% of the time Mike knew what he was doing. The percentage was not quite that high for Andre,” Legg laughed.

By the fourth game of his redshirt freshman year, Legg was going against a Pitt defense full of NFL-caliber players. Lined up across from him was nose guard J.C. Pelusi, and next to him was defensive tackle Bill Maas. One man down from Maas was defensive end Chris Doleman.

That’s sort of similar to what Frazier dealt with last year as a true freshman when he lined up across from Texas’ 348-pound nose guard Keandre Coburn.

“It’s easier to admit now than it would have been back then, but physically, I wasn’t quite ready to play against those level of players,” Legg admitted. “That ’81 season for me was about surviving. When I became a little bit older and stronger, it was much easier from that perspective.”

Koken, too, took his lumps during his first season as a full-time starter in 1986 when West Virginia won just four of its 11 games. Koken said it took him about 10 or 15 games for things to really begin to click, which is about where Frazier is right now in his young Mountaineer career.

By the time he was a senior in 1988, Koken had seen everything and was totally comfortable with anything that was thrown at him. There wasn’t a front he didn’t recognize nor an ID call he couldn’t make.

“There were times when I didn’t even have to make a call because we all knew what we were doing,” Koken said.

Legg said there are some basic qualities a player must have to play center.

“He’s got to be a decent athlete in comparison to other offensive linemen because he’s going to have people in his face so everything happens quicker,” Legg explained. “He’s got to have a little bit of twitch in order to play the position physically, but the mental aspect of it is the biggest thing because for a lack of a better term, he’s the quarterback of the O-line.”

Legg continued.

“You sit practically any offensive lineman down in a meeting room and you freeze a play and you ask them, ‘If we’re running this blocking scheme who are we working to?’ They will all tell you what the ID is going to be,” he said. “But when you are actually playing the position, all of those things happen much, much faster than they happen in a meeting room situation.”

Legg said having Frazier’s football-junkie mentality is helpful for any position on the field.

“The bottom line is to be successful at any position you need to have that mentality. This guy was all-state, but guess what? So is everybody on the team and so is everybody you’re going to play against. How are you going to separate yourself?

“You’ve got to own the position mentally, you’ve got to own the position fundamentally, and technically, and you’ve got to kill it in the strength and conditioning program,” Legg noted. “You not only have to know what to do and how to do it, but you’ve also got to have the physical ability to actually do it.”

After spending a year working for Neal Brown in 2020, Legg got an opportunity to watch Frazier on a daily basis and he was impressed with what he saw. In Frazier, Legg sees some of the same traits he and Koken had when they played for the Mountaineers. He also sees some of the rare physical gifts that Compton, a two-time Super Bowl winner with the New England Patriots, took advantage of during a 12-year NFL career.

“There is no way Kevin Koken or I would have been able to play as a true freshman,” Legg admitted. “Zach is so much more advanced physically compared to us. He was 285 pounds walking in the door for the first time and neither of us weighed 250 when we got here.”

Moore said genetics and getting to campus much earlier have advanced some young offensive linemen’s careers.

“What has made it so much better with offensive linemen is bringing guys in early in June and July to learn the offense and be comfortable in it before August starts,” he admitted.

Having a player who eats, drinks and sleeps football 24/7 doesn’t hurt either.

You’ve got to own the position mentally, you’ve got to own the position fundamentally, and technically, and you’ve got to kill it in the strength and conditioning program.Bill Legg, former Mountaineer center