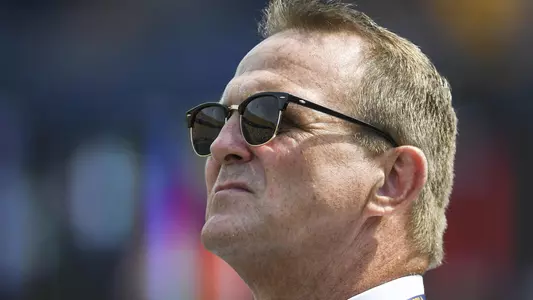

Photo by: Jennifer Shephard

WVU’s Lyons Putting in Long Hours Navigating COVID-19 Pandemic

August 06, 2020 05:12 PM | Football, Blog

MORGANTOWN, W.Va. – Shane Lyons is working three full-time jobs these days and the hours he's putting in are really beginning to add up.

First and foremost, he's West Virginia University's athletics director, of course, who is trying to navigate his alma mater through the country's first major pandemic in 102 years.

He's the chair of the NCAA Division I Football Oversight Committee, which oversees a multi-billion-dollar industry that stands to lose as much as $4 billion with a capital B if the 2020 season is canceled.

And, he serves on the NCAA Council, a high-level group consisting of conference commissioners, athletics directors, senior administrators, faculty representatives and student-athletes responsible for the day-to-day decision making for Division I athletics.

Each entity requires his undivided attention.

"Long hours," Lyons told our Tony Caridi Wednesday during a wide-ranging, 25-minute sit-down conversation on the current affairs in collegiate athletics. "The Football Oversight reports to the Council, but we've scheduled weekly hour-and-a-half phone calls for that, so I have to prep for those calls as well.

"Plus, you are getting calls from around the country just trying to make these models work and how college football is going to work come this September," he added.

Just how it's going to work remains a very fluid situation.

Since the college basketball season was abruptly canceled last March, Lyons has been on a rollercoaster ride – some days he's up and other days he's down.

"You ask me (Wednesday) and I feel a little more optimistic than yesterday. (Thursday) I may feel differently," Lyons admitted. "There are just a lot of days ahead of us and what that means to us and what the virus continues to look like …

"When we start practicing football that will tell us a lot," he continued. "It's another tell-all when students return to campus. There are a lot of safety protocols in place, but we just can't control everything."

Lyons and his AD brethren right now are trying to maintain a delicate balance between conflicting forces – overseeing the health, safety and welfare of the student-athletes, coaches, administrators and fans while also trying to avoid an industry-wide economic collapse that could have far-reaching and lasting consequences.

In 1918, when a flu pandemic forced the cancellation of West Virginia University's football season, it was easy to pull the plug on football, even though the University still tried to play right up until November.

That's because nobody came to the games and they weren't on television.

It was pretty much the same deal in 1943 during World War II when athletics director Legs Hawley used his eraser as much as his pencil to cobble together a seven-game football schedule for a Mountaineer football team consisting mostly of freshman and 4-Fs (men unfit for military service) coached by semi-retired Ira Errett Rodgers.

Hawley made no bones about the product he was putting out on the field that season.

"The brand of play may not be up to par because our squad, naturally, will be composed of young, inexperienced boys," he said, "but since most of our opponents will be in the same position, the competition should be more or less even."

Not exactly words you want to put on your season ticket brochure, but again, the stakes then were nowhere close to what they are today.

Consider this: a study conducted just last year by Tripp Umbach indicated that West Virginia University home athletic events account for more than $300 million in economic activity across the state.

That also amounts to more than $18 million in tax revenue for the state of West Virginia.

In other places the number is significantly more. In nearby State College, Pennsylvania, or Columbus, Ohio, for instance, the economic impact is probably closer to that billion figure mentioned above!

That's why athletics directors from Seattle to Miami have been delaying their decisions as long as possible.

And that's why the Big 12 Conference waited until Aug. 3 to decide how many football games it was going to play this year, ultimately selecting a nine-plus-one model. That's two fewer games than normal.

If the college football season is canceled altogether, athletics departments and universities across the country will be staring into the abyss.

"This is not just a WVU issue," Lyons pointed out. "We're seeing this nationally. I read that Wisconsin is projecting anywhere from a $75 to a $100 million loss as a result of the pandemic."

Lyons said Wednesday his athletics department ended the 2020 fiscal year $5 million in the red due to the loss of revenue from the Big 12 and NCAA men's basketball tournaments, which is just about where the department was projecting to finish.

He said a small reserve was able to offset some of that loss, but fiscal year 2021 is looking much more ominus.

"It's about fans and ticket sales and what that looks like, and we don't have any clear answers on that yet. But using the numbers we have right now starting out it's at least a $12 million deficit, and given what happened earlier this week, losing an additional two football games, it's probably another $5 or $6 million," he explained. "So that's (an) $18 million (loss) playing all 10 football games and playing all of the (men's) basketball games and making sure we get through the championships.

"I don't want to be an alarmist, but that's why we are going to need help as a department from the (Mountaineer Athletic Club) and donations from fans to keep this thing moving forward, because it does cost us a lot from an operational standpoint to keep the department up and running," he said.

As for the safety and welfare of the student-athletes, coaches, support personnel and fans, Lyons has a 360-degree perspective on this.

His son, Cameron, is a college football player at Akron.

Lyons said every effort is being made by athletics departments across the country exploring new ways of minimizing risks as much as possible, from severely reduced person-to-person contact to changes in the equipment the players will be using this fall.

"The helmets are going to have face shields all the way through this fall and our understanding from talking to the medical experts and scientists is the virus is spread through saliva," he said. "You see them in practices wearing the masks, and the face shields on the helmets will serve that purpose.

"You've seen the visors before and now it's the complete face shield. If a student-athlete is talking, (droplets) are going into the face shield and not into the face of somebody else."

Lyons continued, "We've taken the testing, which we will continue to test on a weekly basis … and we are hoping as we get closer to the season there is the antigen test, which is a quicker test than the PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) test involving nasal swabs and so forth. Hopefully, that test becomes more reliable as we get closer to the season."

The fifth-year athletics director indicated a test-reliability rate in the low-to-mid 90% range could make the antigen test a game changer for collegiate sports.

These results would also be almost instantaneous, meaning quarantining and contact tracing will be much, much more effective.

"I think it's going to get there, it's just a matter of time and being patient," he said.

Presently, Lyons said patience has really been the operative word for him and his colleagues.

"It's just taking it day by day and understanding there could be bumps in the road," he said. "There are going to be highs and lows, and we just have to figure out a way to stay in the middle."

First and foremost, he's West Virginia University's athletics director, of course, who is trying to navigate his alma mater through the country's first major pandemic in 102 years.

He's the chair of the NCAA Division I Football Oversight Committee, which oversees a multi-billion-dollar industry that stands to lose as much as $4 billion with a capital B if the 2020 season is canceled.

And, he serves on the NCAA Council, a high-level group consisting of conference commissioners, athletics directors, senior administrators, faculty representatives and student-athletes responsible for the day-to-day decision making for Division I athletics.

Each entity requires his undivided attention.

"Long hours," Lyons told our Tony Caridi Wednesday during a wide-ranging, 25-minute sit-down conversation on the current affairs in collegiate athletics. "The Football Oversight reports to the Council, but we've scheduled weekly hour-and-a-half phone calls for that, so I have to prep for those calls as well.

"Plus, you are getting calls from around the country just trying to make these models work and how college football is going to work come this September," he added.

Just how it's going to work remains a very fluid situation.

Since the college basketball season was abruptly canceled last March, Lyons has been on a rollercoaster ride – some days he's up and other days he's down.

"You ask me (Wednesday) and I feel a little more optimistic than yesterday. (Thursday) I may feel differently," Lyons admitted. "There are just a lot of days ahead of us and what that means to us and what the virus continues to look like …

"When we start practicing football that will tell us a lot," he continued. "It's another tell-all when students return to campus. There are a lot of safety protocols in place, but we just can't control everything."

Lyons and his AD brethren right now are trying to maintain a delicate balance between conflicting forces – overseeing the health, safety and welfare of the student-athletes, coaches, administrators and fans while also trying to avoid an industry-wide economic collapse that could have far-reaching and lasting consequences.

In 1918, when a flu pandemic forced the cancellation of West Virginia University's football season, it was easy to pull the plug on football, even though the University still tried to play right up until November.

That's because nobody came to the games and they weren't on television.

It was pretty much the same deal in 1943 during World War II when athletics director Legs Hawley used his eraser as much as his pencil to cobble together a seven-game football schedule for a Mountaineer football team consisting mostly of freshman and 4-Fs (men unfit for military service) coached by semi-retired Ira Errett Rodgers.

Hawley made no bones about the product he was putting out on the field that season.

"The brand of play may not be up to par because our squad, naturally, will be composed of young, inexperienced boys," he said, "but since most of our opponents will be in the same position, the competition should be more or less even."

Not exactly words you want to put on your season ticket brochure, but again, the stakes then were nowhere close to what they are today.

Consider this: a study conducted just last year by Tripp Umbach indicated that West Virginia University home athletic events account for more than $300 million in economic activity across the state.

That also amounts to more than $18 million in tax revenue for the state of West Virginia.

In other places the number is significantly more. In nearby State College, Pennsylvania, or Columbus, Ohio, for instance, the economic impact is probably closer to that billion figure mentioned above!

That's why athletics directors from Seattle to Miami have been delaying their decisions as long as possible.

And that's why the Big 12 Conference waited until Aug. 3 to decide how many football games it was going to play this year, ultimately selecting a nine-plus-one model. That's two fewer games than normal.

If the college football season is canceled altogether, athletics departments and universities across the country will be staring into the abyss.

"This is not just a WVU issue," Lyons pointed out. "We're seeing this nationally. I read that Wisconsin is projecting anywhere from a $75 to a $100 million loss as a result of the pandemic."

Lyons said Wednesday his athletics department ended the 2020 fiscal year $5 million in the red due to the loss of revenue from the Big 12 and NCAA men's basketball tournaments, which is just about where the department was projecting to finish.

He said a small reserve was able to offset some of that loss, but fiscal year 2021 is looking much more ominus.

"It's about fans and ticket sales and what that looks like, and we don't have any clear answers on that yet. But using the numbers we have right now starting out it's at least a $12 million deficit, and given what happened earlier this week, losing an additional two football games, it's probably another $5 or $6 million," he explained. "So that's (an) $18 million (loss) playing all 10 football games and playing all of the (men's) basketball games and making sure we get through the championships.

"I don't want to be an alarmist, but that's why we are going to need help as a department from the (Mountaineer Athletic Club) and donations from fans to keep this thing moving forward, because it does cost us a lot from an operational standpoint to keep the department up and running," he said.

As for the safety and welfare of the student-athletes, coaches, support personnel and fans, Lyons has a 360-degree perspective on this.

His son, Cameron, is a college football player at Akron.

Lyons said every effort is being made by athletics departments across the country exploring new ways of minimizing risks as much as possible, from severely reduced person-to-person contact to changes in the equipment the players will be using this fall.

"The helmets are going to have face shields all the way through this fall and our understanding from talking to the medical experts and scientists is the virus is spread through saliva," he said. "You see them in practices wearing the masks, and the face shields on the helmets will serve that purpose.

"You've seen the visors before and now it's the complete face shield. If a student-athlete is talking, (droplets) are going into the face shield and not into the face of somebody else."

Lyons continued, "We've taken the testing, which we will continue to test on a weekly basis … and we are hoping as we get closer to the season there is the antigen test, which is a quicker test than the PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) test involving nasal swabs and so forth. Hopefully, that test becomes more reliable as we get closer to the season."

The fifth-year athletics director indicated a test-reliability rate in the low-to-mid 90% range could make the antigen test a game changer for collegiate sports.

These results would also be almost instantaneous, meaning quarantining and contact tracing will be much, much more effective.

"I think it's going to get there, it's just a matter of time and being patient," he said.

Presently, Lyons said patience has really been the operative word for him and his colleagues.

"It's just taking it day by day and understanding there could be bumps in the road," he said. "There are going to be highs and lows, and we just have to figure out a way to stay in the middle."

Ross Hodge | TCU PostgameRoss Hodge | TCU Postgame

Sunday, February 22

Post Game Press Conference | Oklahoma StatePost Game Press Conference | Oklahoma State

Saturday, February 21

United Bank Playbook: TCU PreviewUnited Bank Playbook: TCU Preview

Friday, February 20

Ross Hodge | Utah PostgameRoss Hodge | Utah Postgame

Thursday, February 19