Former Mountaineers Reveling in West Virginia’s Diamond Success

John Antonik

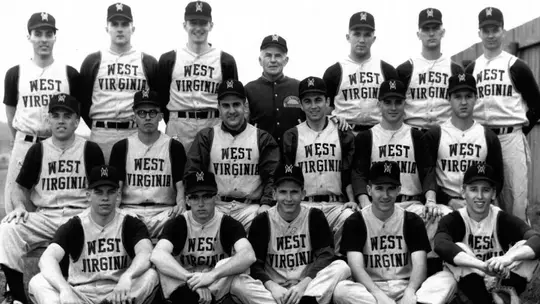

MORGANTOWN, W.Va. – The success of this year’s West Virginia University baseball team has perked up the octogenarians who once played for the Mountaineers back in the early 1960s when WVU was producing some of the best diamond squads in the country.

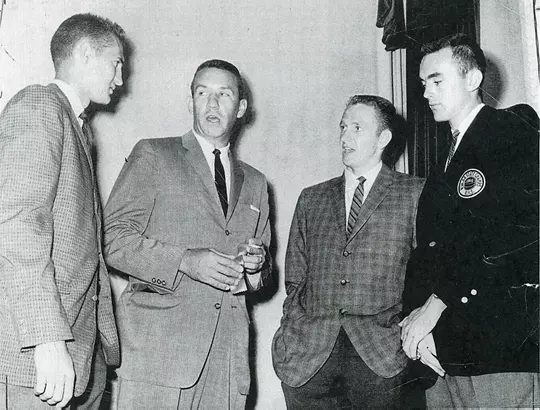

Joe Hatalla, now 83 and living in Orrville, Ohio, just west of Canton, admits to keeping track of his old team on his cellphone. Same with John Radosevich, now living in Ocala, Florida, who said he watches the Mountaineers religiously on ESPN+.

Jim Procopio, who has finally settled down in Parkersburg after 26 different cross-country moves as a professional baseball player and coach, was invited back to a WVU game a few years ago when Randy Mazey was the coach. Procopio said he tries to keep up with the team as much as possible.

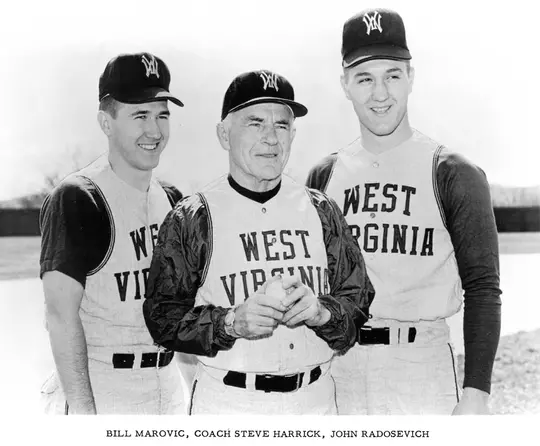

Bill Marovic follows the Mountaineers from nearby Uniontown, Pennsylvania, although he now owns a condominium in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, and his wife has finally convinced him to make the Palmetto State their year-round residence later this fall.

Frank Munchin continues to live in his native Fairmont and watches the games whenever they are on ESPN+.

Even All-American basketball player Rod Thorn still has a passion for all things WVU while spending most of his retired days now living in Florida. Thorn was once a promising first base prospect for the Mountaineers, but more on that later.

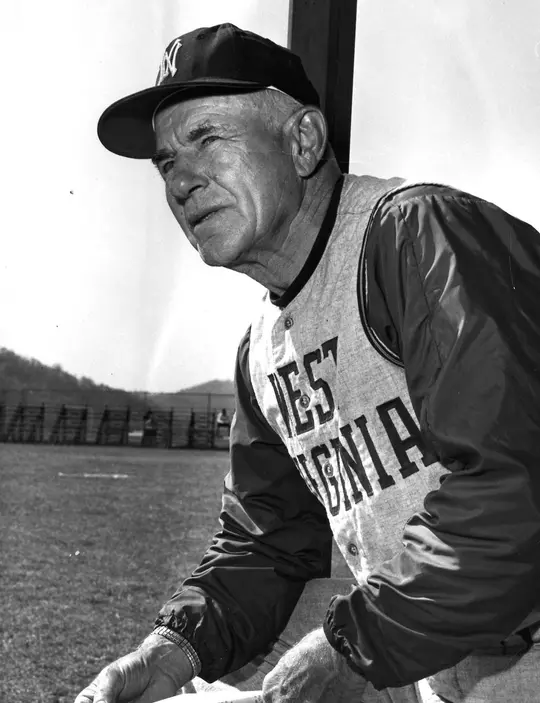

These guys are reveling in the success that first-year coach Steve Sabins is enjoying, while also recalling the special time they once had playing for another Mountaineer baseball coach named Steve - Steve Harrick. Sadly, today, you would be hard-pressed to find many people walking the streets of Morgantown who can tell you much about him. But make no mistake, Steve Harrick is one of the big names in Mountaineer sports history.

How big?

When West Virginia University finally got around to having an all-sports hall of fame in 1991, Harrick was among the nine inaugural inductees along with Jerry West, Sam Huff, Chuck Howley, Ira Errett Rodgers, Joe Stydahar, Red Brown, Harry Stansbury and Leland Byrd.

These guys were the best of the best!

The Fordham, Pennsylvania, native and 1924 West Virginia graduate was 51 when he returned to WVU in 1947 to coach baseball and wrestling after working 14 years at New River State College, today known as WVU Tech at West Virginia University, and the best years of his coaching career were his final six before reaching the state’s mandatory retirement age of 70 in 1967.

From 1961 to 1967, Harrick’s Mountaineer baseball teams won the Southern Conference, advanced to the NCAA Tournament and finished in the top 20 five times. The teams that didn’t reach the NCAA Tournament in 1965 and 1966 were edged out in the league standings by mere percentage points.

From 1962 to 1964, WVU won 73 of 89 games, including an amazing 40-3 road mark. Harrick’s 1963 squad that finished the regular season 29-1, ranked No. 3 in the country, is still considered the best in school history.

Wake Forest, the team that kept Harrick’s Mountaineers from going to the College World Series in 1955, once again knocked the Mountaineers out of the 1963 NCAA District 3 Tournament at Sims Legion Park in Gastonia, North Carolina. Back then, District 3, which included ACC and SEC schools, was considered among the toughest districts in the country.

Until this year, no Mountaineer team has approached what the 1963 squad accomplished.

The players on the team that year were mostly from within 100 miles or so of campus, hailing from such places as Leckrone, Carmichaels, Ronco, Wileyville, Hundred, Meadow Bridge, Cassity and Portage.

Munchin was perhaps the most cosmopolitan of the bunch coming from nearby Fairmont, with a population of about 27,000 in 1960.

These guys all had similar experiences, and they all got along well together. Most of them grew up the sons of coal miners who spent a lot of their time outside on the diamond playing baseball.

“There wasn’t much else to do growing up,” Marovic, pronounced Mah-ROW-vick, recalled.

Where Treatment Plant Road intersects with Locks Hill Road is where Marovic was raised in tiny Leckrone, pronounced Leck-ROANE.

One blink of an eye and you’ve already passed it.

Ronco, where Radosevich grew up about seven miles away from Marovic, was similar. These were tiny villages consisting of people with ethnic last names that were difficult to pronounce.

Radosevich’s summertime activity consisted of bouncing baseballs off the side of the house until his father got tired of it and constructed a makeshift contraption like the Johnny Bench pitchback machine that kids everywhere were using in the 1970s.

“We were too dumb to patent it,” laughed Radosevich, pronounced Rah-DOUGH-suh-vich. “Otherwise, we’d have been rich.”

Radosevich’s father suffered a heart attack during his senior year of high school and the family fell on difficult times.

“Back in those days, coal miners who didn’t work didn’t get paid,” he recalled. “There was no sick leave or anything like that, so we were pretty poor. My mom didn’t work so we just relied on the little bit we could get from the government and a little bit from church. That’s how we survived.”

Despite living just 35 miles from Morgantown, Radosevich said he couldn’t afford the out-of-state tuition to WVU without Harrick coming up with some scholarship money.

Hatalla lived on the other side of Uniontown and played at Carmichaels High, about 15 miles away from German Township High where Marovic and Radosevich starred. Those schools and others have since consolidated into Albert Gallatin High.

Although Hatalla was a couple years older than them, they used to play against each other in summer ball. Hatalla’s Masontown all-stars team won the state championship and finished third at the Little League World Series in 1954, and he also played on a legion team coached by former Mountaineer pitcher Okey Ryan that reached the state finals in 1958.

Ed Tekavec, who was a little older than Hatalla, also hailed from Carmichaels. After some time in the service, Tekavec played for Harrick at WVU from 1960-62. As a matter of fact, from 1960 until Harrick retired in 1967, there were about a dozen or so guys from the Uniontown area who played baseball for the Mountaineers.

Hatalla recalls an abundance of other good local ballplayers such as Jack Smodic, the Korcheck brothers, Steve and Mike, and Bruce Del Canton from nearby California.

Del Canton pitched 11 seasons in the majors with the Pirates, Royals, Braves and White Sox.

Incidentally, West Virginia used to have some knock-down, drag-out midweek games against the smaller local schools like California State, West Liberty and West Virginia Wesleyan because there were so many good players in the area. Radosevich and West Liberty’s Joe Niekro had some epic encounters when the Hilltoppers won the national NAIA championship in 1964.

“A lot of these guys were good enough to play in the minors, but there was no money, and they had to go and get a job,” Hatalla explained. “They couldn’t raise a family or do anything with it.”

On the other side of the Pennsylvania state line down in West Virginia is where Ron Renner and Jerry Milliken grew up in Hundred. Driving farther west across Route 7 deeper into Wetzel County is how Harrick found pitcher Frank Haynes in Wileyville.

Outfielder Phil Douglas was from Elkins, while pitcher Joe Jeran came from just south of there in Cassity.

Pitcher Dave Wilson hailed from Keyser.

Infielder Mike Dyer’s hometown was Parkersburg, a short drive down Route 2 along the Ohio River from where Jim Procopio played football and baseball at St. Marys High. Procopio came to West Virginia on a football scholarship.

“When I was in high school in St. Marys, I didn’t pay much attention to West Virginia baseball,” Procopio admitted. “Now every Saturday with Jack Fleming, I was working in my dad’s shoe shop, and we always had the football games on the radio. Football-wise, that’s where you always wanted to go, and baseball was something that came along with it if you could work it out with the coaching staff.”

Which Procopio did, along with husky fullback Steve Berzansky, from Cambria County in Pennsylvania close to Johnstown. Berzansky began his collegiate career playing football for Frank Kush at Arizona State before transferring to WVU.

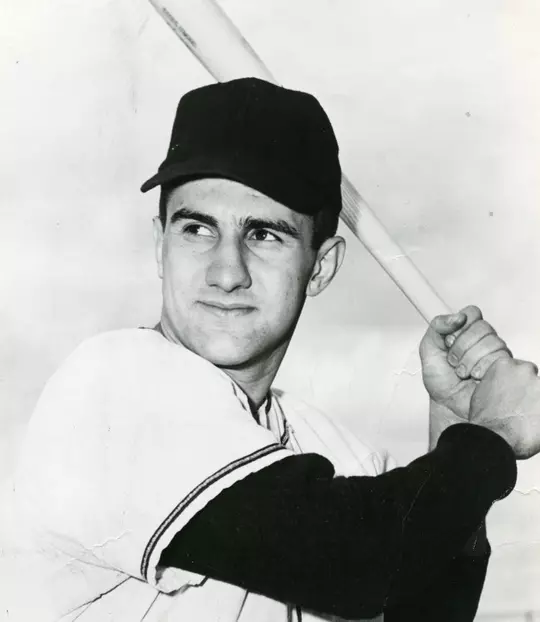

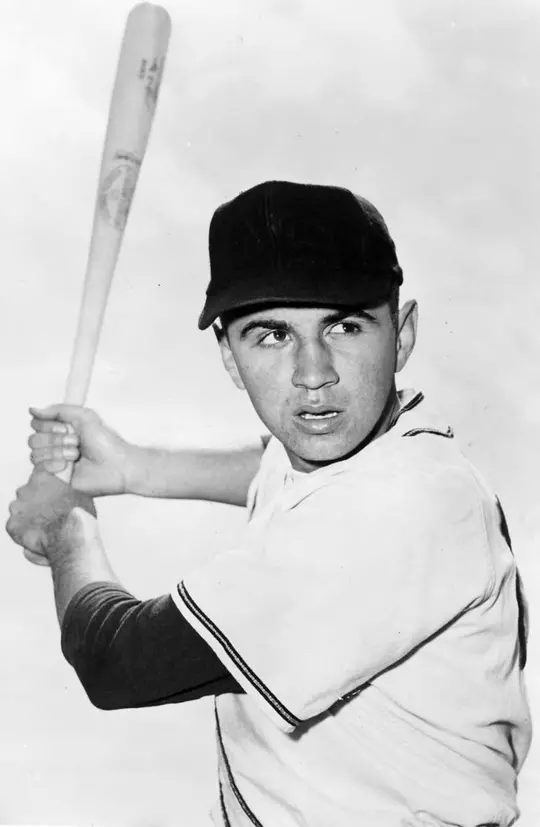

Thorn was one of the nation’s top basketball recruits coming out of Princeton High in 1959 who was proclaimed a “natural resource” by the state Legislature as a way of fending off overtures from Duke. He eventually joined the Mountaineer baseball team during his junior season in 1962.

Thorn batted third in the lineup and played first base that year.

Pitcher Wendell Backus was from Meadow Bridge, in eastern Fayette County, and shortstop Dale Ramsburg came from far-away Frederick, Maryland, although Harrick discovered him when he was playing at Potomac State Junior College.

Harrick thought so much of Ramsburg that he recommended him for the Mountaineer job after his retirement, and Ramsburg remained at West Virginia until he succumbed to cancer in the fall of 1994. Former Pitt coach Bobby Lewis once said that the only difference between Harrick and Ramsburg was that Ramsburg was a little more liberal; Dale used three baseballs during games, while Steve only played with one!

Pitcher Vince Parziale was from DuBois, Pennsylvania. Infielder Gordon Whitman came from St. Albans and infielder Jeff O’Neil was from Morgantown.

Those were the 19 players who made up the West Virginia University baseball team in 1963. There are actually more pitchers on this year’s squad!

Harrick had no assistants, and he often relied on some of the older players to help get them organized. Hatalla was one of the older guys Harrick trusted in 1963.

“He was coaching by himself, he needed some help, and he recognized that,” Hatalla said. “We knew what he wanted done and why he wanted it done.”

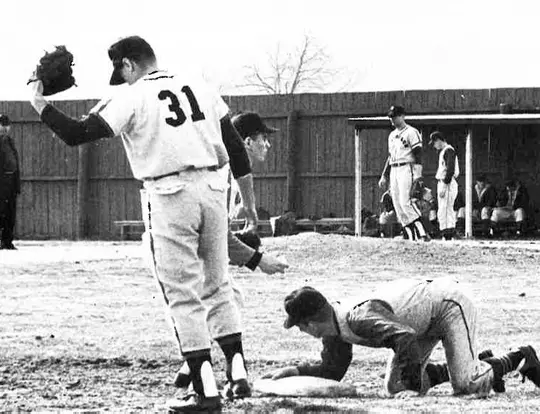

“The biggest thing coach did happened before we ever got on the field,” recalled Procopio, who now has a high school field named after him in Amherst, Virginia. Procopio also managed minor league teams in the Braves organization. “He made you show up, go to class and get your ass to practice. Then, we went through fundamental drills, cutoffs and relays to the point where it was coming out of your ears.

“I took those things with me when I started coaching baseball, and they made a big difference,” Procopio added.

If a player had a flaw, Harrick worked with him until he fixed it. If he couldn’t, then another guy took his place in the lineup. He always found a spot on the field for his best players.

Harrick saw Munchin pitching in the state American Legion tournament in Charleston and recruited him to WVU as a pitcher, but eventually, he thought Munchin’s strong arm better served the team in right field.

“Coach Harrick was a helluva coach,” Munchin explained. “With all our classes, our practice times varied, and he would be out there from one o’clock until six. I don’t know if he ever put that fungo bat down.”

During games, there were some non-negotiables. If he told a player to take two strikes before swinging, the player was expected to take two strikes. If he was given the green light to swing on a 3-0 pitch, Harrick expected the ball to be hit hard somewhere in the gap.

If you didn’t, then there were consequences.

Muchin said he once hit a 3-0 pitch on the nose directly to the right fielder, who caught it. An upset Harrick told him the ball should have been hit into the gap.

West Virginia’s baseball field didn’t have dugouts, and Harrick managed games from the third base bench. Players he trusted coached the bases. The bunt signal was simply Harrick standing up and kicking his leg. If you missed the bunt sign more than once, he would jump up off the bench, call timeout and walk over to the batter and say in a voice loud enough for everyone to hear, “Bunt the damned ball!”

When Marovic led the country in stolen bases in 1964, Harrick’s steal sign was him getting up, looking at Marovic standing on first base, and pointing out toward the second base bag.

He expected Marovic to be standing on it by the time he sat back down.

Harrick never called a pitch or even suggested one during the 86 games Procopio caught for the Mountaineers in 1961, 1962 and 1963. Harrick, in a syrupy, grandfatherly voice that sort of sounded like a mixture of Jimmy Stewart and Ronald Reagan, would say, “Welllll Jimmy, you are doing a fine job.”

Procopio was one of the team’s pranksters and was usually in the middle of some sort of caper, whether it was short-sheeting Harrick’s bed on a road trip or coming up with the brilliant idea of getting married before a home baseball game, which he actually did.

Procopio and best-man Tom Stepp were late arriving to the game after Procopio’s morning wedding in Maryland, and afterward, the new bride was forced to sit in the stands and watch them play. Procopio made it up to her by taking her on a honeymoon to Fairmont. Sixty-some years later, they are still happily married!

Radosevich, the 90th overall pick in the fifth round by the Los Angeles Dodgers in the first-ever Major League Draft in 1965, holds most of the school’s strikeout records, including the 22 Waynesburg batters he fanned during one game in 1965. But as a sophomore, he once shook off a pitch Procopio had called and Procopio immediately took issue with it.

“He called timeout, walked out to the mound and said, ‘My job is to call the pitch, and your job is to throw it, so don’t you try and do my job!’ I never shook him off the rest of the year,” Radosevich laughed.

The grip Radosevich used to throw his fastball was the same one he used to throw his curveball. Consequently, everything he threw moved – inside on the hands to left-handed hitters and outside and tailing away to righthanders.

“I would set up inside and he would throw that damned tailer away, and I was all over the place trying to catch it,” Procopio laughed. “But he had a helluva arm.”

Munchin said Backus was a big, old country boy with an unbelievable 12-to-six o’clock breaking ball that started out shoulder-high and ended up near your ankles.

Wilson and Jeran were the team’s ace pitchers, combining to win 14 of 16 games with Jeran posting a 1.16 earned run average in ‘63. Wilson’s ERA was 2.44.

When Radosevich wasn’t starting midweek games, Harrick often brought his sophomore into contests late when his starters got tired, and the score was close.

There was no such thing as closers back then, and saves were not counted as an official statistic, but Radosevich basically served that role during the ’63 season. He pitched a scoreless eighth and ninth inning in West Virginia’s 2-1 victory over 18th-ranked Auburn, knocking the Tigers out of the NCAA Tournament.

The lefthander also shut down late rallies against Lynchburg, George Washington and Penn State and finished the season with an 8-0 record.

The regular lineup consisted of Marovic playing center and hitting leading off, followed by Hatalla at second base. Procopio caught and batted third, with first baseman Berzansky in the cleanup spot behind him.

Ramsburg played shortstop and hit fifth. Munchin, in right, batted sixth, followed by Dyer at third base batting seventh and left fielder Phil Douglas in the No. 8 spot.

Berzansky led the team with 41 hits, 14 extra base hits and a .360 batting average. Procopio batted .355 with a team-best five home runs and 36 runs batted in.

Hatalla and Ramsburg also hit better than .300.

Berzansky, Hatalla, Procopio and Jeran were named to the All-Southern Conference First Team while Marovic, Radosevich and Wilson were second team choices.

But the one key player missing in the lineup that year was Thorn, whose baseball career ended five games into the ’63 season against West Virginia Wesleyan.

In the sixth inning of a scoreless game, there was a popup between home and first base that Thorn felt he should have caught. Procopio ended up catching it, and while trying to pick off the runner at second base, his throw struck Thorn on the side of the head. Had it hit his temple instead of his ear, it might have killed him.

“Rather than hitting the dirt, I just leaned my head over to the side; he threw the ball, and it hit me in the ear,” Thorn recalled. “It didn’t knock me out, but my inner ear was affected and every time I moved my head, I threw up.”

Thorn was admitted to the hospital and spent several days there until he was finally released. At the time, he was considered a top NBA prospect and was eventually picked No. 2 overall by the Baltimore Bullets.

“I was unable to do anything until the summer was almost over,” he explained. “Every time I moved my head, I got dizzy. About two weeks before training camp, I got so I could move around and finally do some things. But I was not nearly ready to play, and I probably wouldn’t have made the team if I hadn’t been a first-round pick.”

Had he not gotten hurt, Thorn said he would have played the entire season and probably would have pursued a professional baseball career afterward. He turned down offers to sign following his junior season in 1962 to play his senior year of basketball for the Mountaineers, and he had additional baseball offers following his rookie season with the Bullets in 1964.

Based on the discussions Thorn had with professional teams, he believes he could have gotten a bonus close to what former Mountaineer second baseman Paul Popovich received to sign with the Chicago Cubs in 1960, which was about four times more than the $12,500 Thorn made during his rookie year with the Bullets.

“If I had to do it over again, I probably would have (signed a professional baseball contract),” he admitted.

Thorn’s teammates felt losing him early in the season was a big blow to the team. Although Berzansky filled in well at first base, Thorn would have provided another big bat in the lineup that could have meant more home runs and additional power in the gaps.

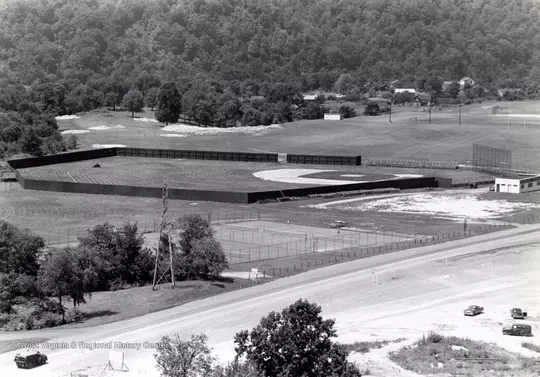

Those homers weren’t coming at cavernous Hawley Field, though.

Sitting where the WVU Coliseum is now located, Hawley Field was a pitcher’s dream and a power hitter’s nightmare. According to the players, it was anywhere between 330 and 350 down the lines, 385 to 400 in the power alleys and 415 to straight away center.

The wind frequently blew across from right field into the batter’s face, knocking down anything that was hit to right. Procopio admits that’s how he became such a proficient opposite-field hitter in the pros by learning to go the other way.

“My God, I hit two home runs my entire career there,” he said. “I was a left-handed hitter, and the one thing it taught me was to hit the ball in the left center gaps instead of just being a pull hitter. And back in those days, I could run a little bit.”

“Playing centerfield, there was just as much room behind me as there was in front of me,” Marovic recalled.

A wooden fence encapsulated the entire field with bleacher seating along the first- and third-base lines, as well as some seats behind home plate. There was a white concrete building behind the third-base bleachers where fans and players could use the bathroom or take shelter when it was either too cold or raining.

Tennis courts were located beyond the left-field fence near where the Core Arboretum is today, and grass practice fields for the football team were constructed behind the baseball diamond. The third-base line basically ran parallel to Route 19 leading out of town.

The players dressed down at the old field house on Beechurst Avenue, and those who didn’t own cars, either walked or jogged the mile and a half that it took to get up to the field for practice. Back then, automobiles were a crucial part of the baseball program, which operated on a shoestring budget. Eventually, the University was forced to switch to vans and buses in 1964 when five people, including Harrick, were involved in an accident on Route 73 about 10 miles east of Morgantown.

One of the players, first baseman Jim Willetts, was paralyzed from the waist down because of the injuries sustained in the wreck.

Prior to the accident, for long road trips Harrick arranged a convoy of cars that included himself, assistant athletic director Lowry Stoops, trainer Whitey Gwynne and one or two of the older players. Hatalla had the responsibility of driving one of the cars in 1963, and the following year, Ramsburg was assigned the task before the wreck.

There was a hierarchy to road trips. The sophomores and the guys who normally didn’t play much were forced to ride with Harrick, who talked baseball from the moment they left town until they ended up wherever they were going.

Stoops was next in line.

If it wasn’t Hatalla’s, then Gwynne’s car was the one the older players wanted to ride in because Whitey usually had a girly magazine or two underneath the seat and enough R-rated stories to get you from Cumberland, Maryland, to Richmond, Virginia.

When Procopio was a sophomore riding with Harrick, they were supposed to go directly to church the night before the game so Harrick could attend the late mass. He was a devout Catholic who never missed mass at St. Theresa’s Church near campus.

“We pull up, and he says, ‘Well boys, they must have heard the Mounties were coming because the lights are on.’ It was a damned Holiday Inn that we pulled up to!” Procopio laughed.

Occasionally, Harrick would ride shotgun and let one of the players drive. Once, after talking himself to sleep, Harrick’s head was resting on the back of the seat with one of his large cauliflower-marked ears exposed. Sitting behind him was practical jokester Bobby Peyton, who stuck out his tongue near Harrick’s ear to try and get the other guys to laugh.

The driver, seeing Peyton doing this in his rearview mirror, quickly jerked the wheel, causing Harrick’s head to move and Peyton’s tongue to go directly into his coach’s ear. The startled Harrick immediately woke up, looked at the other players and exclaimed, “My Bobby, aren’t we getting awful affectionate today!”

The Steve Harrick stories are endless.

One of the players didn’t realize until his senior year that Penn State coach Joe Bedenk’s first name was actually Joe. Although Harrick and Bedenk were friendly around each other, whenever Harrick was sitting on the bench glaring across the diamond at his counterpart, it was always, “(Expletive) Buh-DINK!”

Once, after Virginia Tech won the first game of a doubleheader in Blacksburg, coach Red Laird wanted to call off the nightcap because it was starting to snow. Harrick refused.

“We gave you the damned first game, so we’re playing the second one!” he growled.

The coach kept himself in terrific shape, never letting his weight go above 160 pounds. He would skip rope for a half-hour each day after practice before showering with the players down at the old Field House.

There was certainly more gas left in his tank when he was forced to retire in 1967. Harrick could have easily coached another five years or so, but he would have been involved in a complete program rebuild because the baseball field was one of the casualties when construction began on the new WVU Coliseum. Harrick’s remaining years would have been spent coaching the team on a high school field until the new field was built below the Coliseum in 1971.

“He was such a good man to play for, and he was the godfather to my oldest boy,” Procopio said. “I just respected the man because he always respected his players. I never heard anyone say, ‘Oh God, Harrick!’”

“One of the biggest disappointments in my life was never getting coach Harrick to the College World Series,” Hatalla said. “He was such a great guy. You couldn’t ask for somebody better to play for because he always pushed you to the limit, and sometimes beyond. We were all better people when we left there having played for him.”

“When I played for him, it was during his waning years, so to speak,” Radosevich said. “But he was a wonderful man, a very good role model and all the players just loved him.”

Following retirement, Harrick continued to live in Morgantown with his wife, Della, helping organize the local Babe Ruth and Little League baseball teams and also doing some area scouting for the Boston Red Sox.

He was active in the Morgantown Rotary Club and served as the chairperson on the Children’s Committee responsible for raising funds and putting on the annual Christmas party for underprivileged youngsters.

Harrick remained active in the community right up until his death on Dec. 7, 1988, just 19 days before his 92nd birthday.

“He was such a wonderful human being. He had those ears that were like wrestler’s ears, and I just loved playing for him,” Thorn remembered.

Harrick was inducted into the Helms College Baseball Hall of Fame in 1967, the Helms Wrestling Hall of Fame in 1969 and the American Baseball Coaches Association Hall of Fame in 1975.

Making the occasion even more memorable was longtime friend and classmate Art Rooney giving Harrick’s introduction speech just days after his Pittsburgh Steelers defeated the Dallas Cowboys in Super Bowl X.