40th Anniversary of Ed Etzel’s Gold-Medal-Winning Performance Looms

John Antonik

MORGANTOWN, W.Va. – A very young, and very wet-behind-the-ears Tony Caridi was once given the assignment of interviewing Dr. Ed Etzel, West Virginia University’s gold-medal-winning rifle coach.

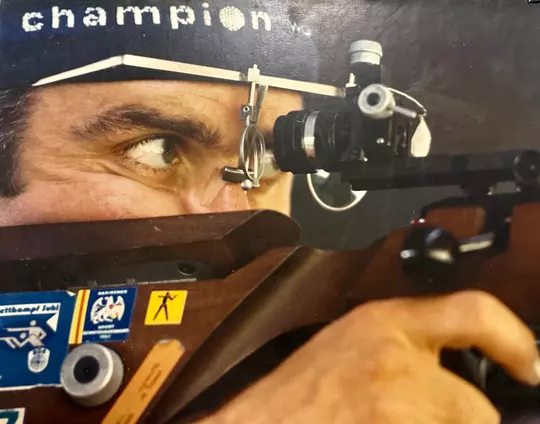

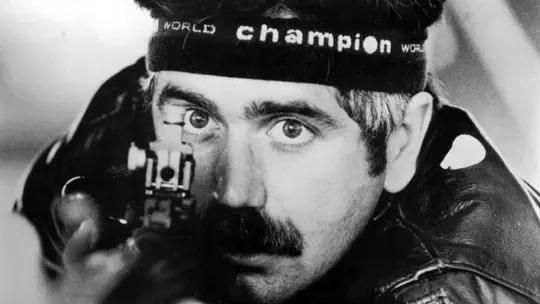

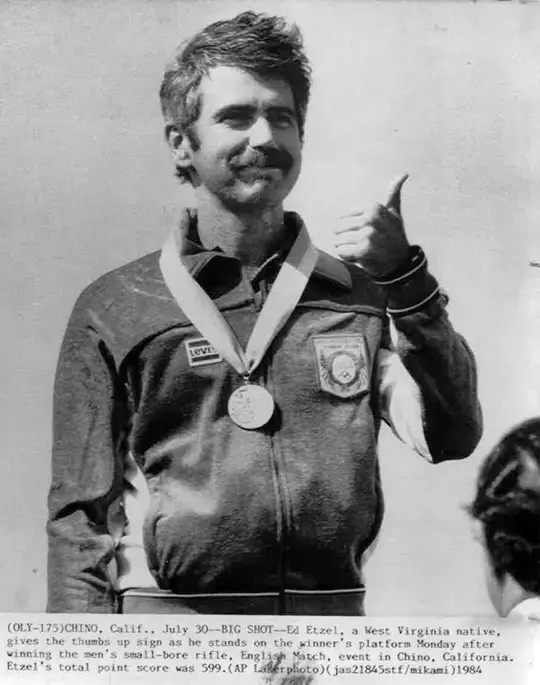

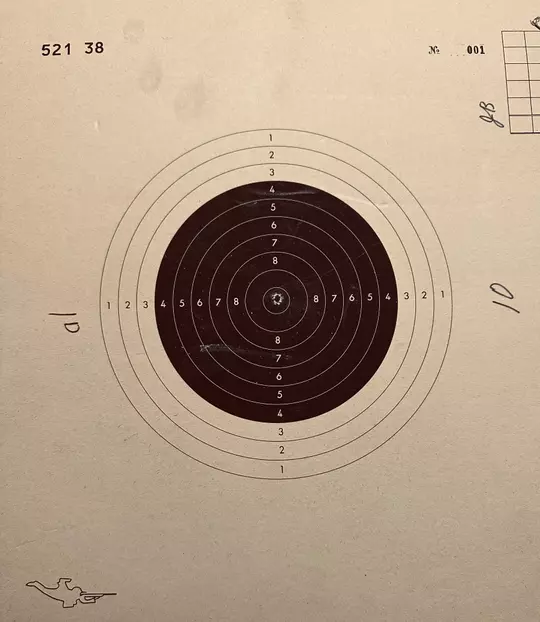

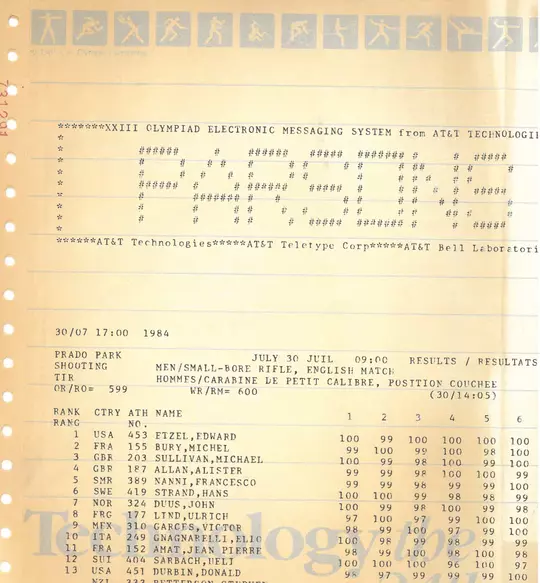

Etzel had come within a point of registering a perfect score of 600 in the English Match smallbore rifle event at the 1984 Summer Olympic Games at the Prado Recreation Arena in Chino, California, located about an hour’s drive east of Los Angeles.

His 599 tally, which some thought could have actually been a perfect score because targets back then were visually inspected, had established an Olympic record at the time. He fired 60 shots from a prone position at a distance of 50 meters.

Etzel was the first Morgantown resident to win a gold medal in the Olympics, and at the time, he was one of just three with West Virginia University ties to do so – the others being basketball superstar Jerry West in 1960 and shooter Jack Writer in 1972.

Because he was among the first Americans to win a gold medal at the ‘84 Games, his media demands were off the charts for an Olympic shooter. A 3 a.m. limo ride to Hollywood to be a guest on “Good Morning America” followed, as well as profiles in the New York Times and other major U.S. newspapers.

“It was blurry for me after winning the medal because, as is probably the case, everybody wants a piece of you so to speak,” Etzel said recently. “We had no media coordinator. We had a coach in name only, so we were pretty much on our own.

“They’d say, ‘Okay, ABC wants to do this’ and ‘this person from the New York Times wants to do that’ so that was very distracting doing all that other stuff. I ended up placing 15th in the other event that I qualified for,” Etzel recalled.

“I did have a colleague of mine tell me that I needed to be careful what I was doing, and I said, ‘Well, I really don’t know what I’m doing,’” he mentioned. “There was no one intervening at all, and it wasn’t like I was getting paid for any of this stuff. I really was just kind of winging it.”

Once Etzel had returned to Morgantown and Caridi finally tracked down the city’s newest celebrity, the young reporter’s opening question to him was something to the effect, “Winning a gold medal certainly has to be one of the highlights of your life?”

To which Etzel replied, “Well, Tony, I don’t know about that, but it certainly made my afternoon.”

Even today, now 40 years later, whenever the two run into each other at the grocery store or someplace else around town, Caridi always asks Etzel, “So, Ed, how is your afternoon going?”

They laugh, say hello to each other, and then go about their business.

Appreciating Ed Etzel’s sense of humor probably requires at least a 1,400 score on the SAT, but if you get it, the laughter is non-stop.

He relates a funny story about the three medal-winning shooters needing to rehydrate themselves to provide urine samples for the Olympic drug testers. Apparently, having water available to shooters was not a huge priority back then, so the person coordinating the drug testing cracked open a case of Budweiser and handed each of them cold cans of Bud to help the process along.

Ed being Ed, he asked for two.

“Can you imagine doing that now?” he laughed. “I know all three of us standing on the podium had at least one.”

Etzel’s moment in the sun was only brief, however, because tiny Mary Lou Retton, who grew up just down the road from Morgantown in nearby Fairmont, had taken the state and nation by storm that summer with her amazing, gold-medal-winning performance in the women’s gymnastics all-around competition.

Mary Lou’s itinerary after the Olympics included appearances on the “Tonight Show” and at a star-studded gala in Los Angeles thrown by Bob Hope.

Nearly 20,000 people showed up in Fairmont to see her take part in a three-hour motorcade, and an even bigger parade was scheduled in the state’s capital city, Charleston, which was organized by local politicians, including Gov. Jay Rockefeller, who was then running for the U.S. Senate.

Etzel, meanwhile, flew into Morgantown’s Hart Field to a small reception of friends waving American flags and some others at the airport who joined in when they realized that they were in the presence of an Olympic gold medalist.

Someone down in Charleston soon realized that the state had two gold-medal winners, so Etzel was quickly added to the Charleston parade and rode in another car behind Mary Lou.

“We both had on our Olympic uniforms and our medals, and we ended up with the mayor,” Etzel remembered. “We got keys to the city and then they had a reception inside a car dealership with a lot of people in there. They turned to Mary Lou and uncovered a new red corvette that they gave her. Then, they turned around and thanked me for winning the gold medal.”

For Etzel, making just $16,000 a year coaching the WVU rifle team and bumming rides to work every day because his old car had conked out, it was a rather humiliating experience, despite being the best shooter in the world at the time.

Etzel, who grew up in New Haven, Connecticut, began shooting at age 11 when he was a member of the Boy Scouts. He improved his marksmanship at the Jack Lacey Club and became good enough to attend rifle powerhouse Tennessee Tech, where he was an All-American shooter.

A stint in the military where he was stationed in Fort Benning, Georgia, in the U.S. Army Marksmanship Unit preceded his hiring at WVU in 1976. Etzel achieved the rank of second lieutenant before being honorably discharged.

“I began in mechanized infantry, which was not very fun, and Vietnam was still going on when I began active duty in 1974,” he recalled. “The unit I was assigned to had just come back from combat and a lot of those guys were really a trainwreck. Now that I think about it, that may have been the time when I started to think about being a psychologist because I listened to people a lot, and it was some pretty horrific stuff.”

In the meantime, he continued shooting and won gold medals at the 1978 World Championships and 1979 Pan American Games, but as far as coaching the WVU rifle team, his Mountaineer squads were struggling to get over the hump.

His alma mater was the dominant program in college rifle at the time, when the NCAA took over the sport from the NRA, while West Virginia was getting a reputation for being annual bridesmaids to the Golden Eagles.

In 1980, the year the NCAA hosted its first rifle championship, Tennessee Tech easily bested second-place West Virginia in the final standings. A year later, WVU reduced the margin to three points, and in 1982, the Mountaineers came within two points of claiming the title.

Etzel’s 1983 squad, led by NCAA smallbore champion David Johnson, finally captured the first NCAA championship in school history in any sport.

Then, just 16 months later, Etzel stood at the top of the Olympic podium one rung higher than France’s Michel Bury and two rungs above Great Britian’s Michael Sullivan, who bore a striking resemblance to Gordon Pibb, the know-it-all athlete from Average Joe’s Gym in the 2004 hit comedy movie “Dodgeball.”

By the time Etzel stepped aside in 1989, the Mountaineers owned five NCAA titles, four coming under his watch. A fifth was overseen by Greg Perrine, who was filling in for Etzel while he was on sabbatical pursuing his doctorate degree in psychology.

East Tennessee State graduate Marsha Beasley was Etzel’s handpicked successor, and she led the Mountaineers to eight national championships over nine seasons from 1990 to 1998. Current coach Jon Hammond has contributed six more national titles since then, giving WVU a total of 19 NCAA rifle championships.

The Mountaineers have either won or placed second in 28 out of the 44 championship events the NCAA has conducted in rifle. No other program in any sport can match West Virginia University’s dominance.

And the roots of this amazing run of success took hold during a year-and-a-half period from March 19, 1983, when WVU claimed its first rifle title, until July 30, 1984, when Etzel won an Olympic gold medal.

“Yeah, things did happen pretty quickly,” Etzel admitted. “The success I had, I think, helped recruiting.”

Etzel believes the seeds of success were probably sown a few years prior when Sweden’s Stefan Thynell competed in the 1976 and 1980 Olympic Games.

“At that time, he was just head and shoulders above everybody else, and he was the guy who really tipped things in the direction it took,” Etzel recalled. “Soon, others came in after him and most of them are now in our (WVU Sports) Hall of Fame. The other thing that helped is we actually got a rifle range in the Shell Building.

“The place we had before (located underneath the bridge attached to old Mountaineer Field) you could literally shoot rats down there. It was that kind of thing,” he said.

Sometime after Etzel’s third national championship in 1986, he requested a meeting with WVU athletic director Fred Schaus. He wasn’t making much money at the time as the rifle coach, was becoming weary of transporting his athletes in University-issued vans to all their competitions and was growing a little restless.

Etzel felt his life’s calling was pursuing psychology and helping others.

“It was a big risk,” he admitted. “I went to talk to Fred, and I said, ‘Look, I’m going to become a psychologist, and I’d like to retire from coaching, and you are going to need to find somebody else. In the meantime, this is what I think needs to be done here. Here is what Ohio State is doing (in sports psychology). Here is what Washington is doing, and this is something that’s going to be really important.’

“To a lot of people, that was like selling snow to Eskimos, but Fred said, ‘Alright, I’ll hire you to do that, and I’ll pay you $15,000 a year.’ I was also working as an assistant professor in the School of Physical Education, so I got my doctorate and that was a big leap right there.”

Etzel began sports psychology for the Athletics Department, which also involved the Life Skills program and other helpful support services for Mountaineer student-athletes. He remained a University professor until his retirement in 2019.

“When I gave up coaching, I’m just as proud of what I accomplished with mental health, sports psychology and the life skills stuff, and that’s sort of lost in the haze of things,” he said proudly.

On July 30 – the 40th anniversary of Etzel’s gold-medal-winning performance - he and his wife, Anne, whom he refers to as “the missus,” will probably spend the day just like every other – in low-key fashion, perhaps watching rifle’s Mary Tucker, one of eight current and former WVU athletes competing at this year’s Olympic Games in Paris.

Anne, incidentally, is Professor Emeritus in the WVU School of Medicine and is Executive Council Chair of the School of Medicine’s Alumni Association.

Ed's gold medal, now sitting in a safe, used to hang on the refrigerator door, and he would let people wear it whenever visitors came over to the house. He would also take it to the (Mountain State) Forest Festival or to CB&T Bank in Morgantown - his only commercial endorsement for winning a gold medal. Etzel was required to come into the lobby occasionally wearing his Olympic outfit and gold medal and sign autographs for customers.

The only significant gift Etzel ever received was a 1984 Ford Bronco II after some local Coors dealers throughout the state chipped in money when it became known that he didn’t own a reliable car. Etzel credits former WVU staffer Jay Redmond for getting that done.

“Man, I drove that thing for a long time,” Etzel said. “I was extremely grateful for that gift.”

Etzel is also willing to let everyone in on a little secret - the gold medal that he won is not really made of gold.

“John Kuehn, who is still a jeweler here in town, I brought it to him once and I asked him, ‘Hey, can you tell me what this thing is worth?’” Etzel began. “He said, ‘Do you mind if I scratch it?’ I said, ‘No, I don’t care what you do with it.’

“So, he takes a sample from it, and he says, ‘Well, it’s actually not gold. It’s an inert metal that has been sprayed with gold. So, I asked him what it was worth, and he said, ‘Ahh, maybe 30 bucks.’”

Etzel said someone once told him that his medal would make a great neckless.

“Well, that’s not going to happen,” he laughed.

Since retiring, Etzel, now 71, has remained busy working as a DJ for the campus radio station WWVU-FM hosting various weekend shows, including the popular “Time Warp.” He’s been doing this for the last 18 years.

“From the beginning of rock’n’roll to the 1980s, and I do a blues show on Sundays,” he said. “We’re kind of like SiriusXM. The two shows, the Americana Show is 8 to 10 in the morning on Sunday and from 10 to 12 is blues. We have a platform called Radio Jar that allows us to create set lists and then insert curations … ‘Yeah, we’re going to listen to Robert Johnson and then we’ll hear from B.B. King.’ I have my radio voice.

“I really mix it up, and we’ve got a lot of listeners from all over the place because of the app and the Internet. (Music) speaks to our soul, or maybe it’s a reflection of it,” he said.

Etzel took up golf and played obsessively to the point where he became an 8-handicapper, but his afternoons are now usually spent painting, gardening or playing his guitar. One of his watercolors is currently being auctioned off to benefit the West Virginia Botanical Garden located off Tyrone Road just outside of Morgantown.

Every now and then, Ed allows himself a moment to think about that memorable time out in Los Angeles, but not too often, he admits.

“Yeah, well I’ve been pretty busy,” he said.

Pretty busy enjoying his afternoons, hopefully.